Polls and Campaign Narratives

Felonies! Assassination attempts! Debate match-ups! With less than two months to go, the 2024 presidential race has already had its fair share of front-page moments – but which will truly stick with voters?

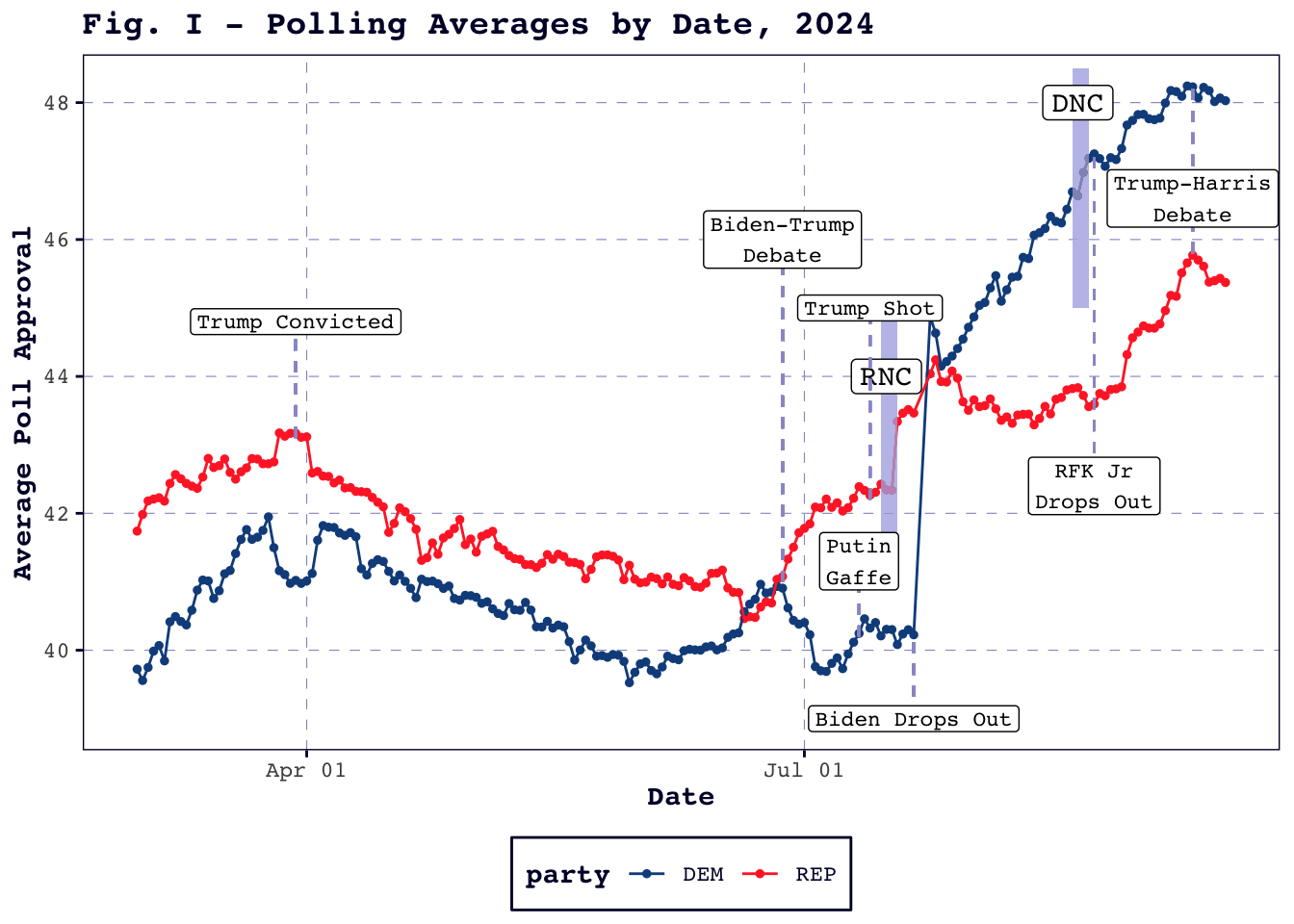

Figure I (below) plots some newsworthy events from the past several months against the candidates’ performance in national polls.

In some cases, the graph lends itself to story-driven interpretations: there is, for instance, President Trump’s short-lived bump in approval around the time of his conviction and the dramatic blue spike where Vice President Harris first assumed the role of presumptive candidate in lieu of Biden.

At other times, however, the polls defy the headlines. The first assassination attempt against President Trump is virtually indistinguishable in this aggregation. While Biden’s numbers were already low in early July, confusing Presidents Putin and Zelensky – not to mention his opponent and his own vice president – did not perceivably worsen his standing in the polls. Even the DNC, with its splashy line-up of Democratic stalwarts and Republicans for Harris, fades into the background.

Notice, too, how close the polls remain across these data. Even when one candidate has a particularly good week or month, they tend to remain within a scant few points of their opponent.

Polls can sometimes seem like a cheat code; a no-nonsense way to get into the minds of the electorate and satisfy our curiosity long before Election Day hands down its verdict. But as these inconsistent trends suggest, polls are deeply imperfect. They are swayed not just by what “should” matter – policy proposals, scandals, good or bad speeches – but also by the framing of the poll itself.

Do the pollsters have a partisan bias? How do they adjust their raw data, if it is lopsided demographically or politically? Will their respondents actually turnout in November? If they do, will they change their minds? All of these answers have powerful implications for poll-dependent forecasts.

The dull truth is that polls lie somewhere between magic bullet and useless drivel. My prediction for this week, like the graph above, uses simple aggregation to curb the effects of potential outliers among the major pollsters, and incorporates a measure of fundamental economic conditions to account for the influence of broad, retrospective evaluation on voter behavior.

Predictions and Methodology

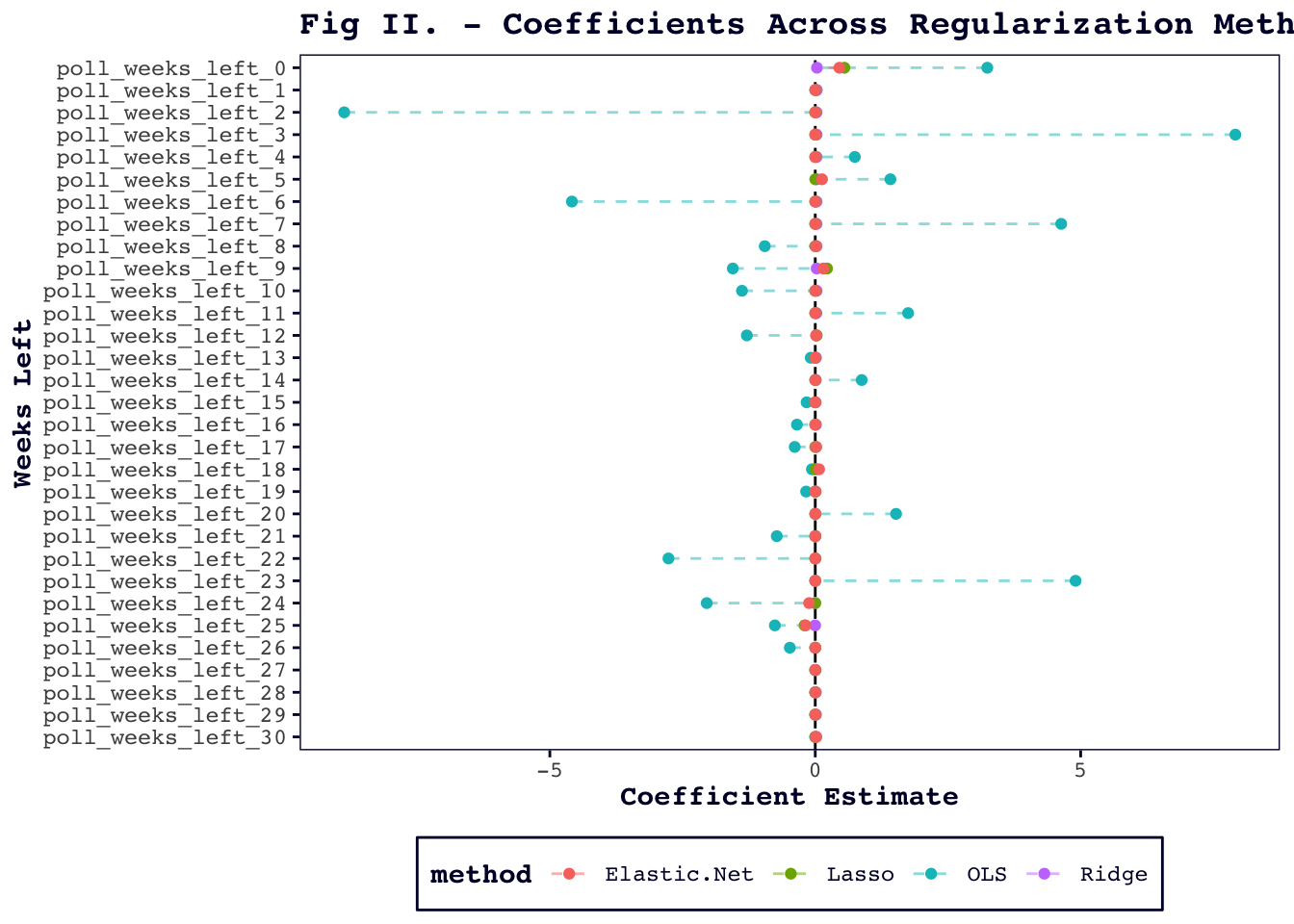

For my first prediction, I looked at week-by-week poll aggregations. Incorporating every single week into a plain OLS regression, however, would have created a dimensionality error since there are so few election years in the dataset compared to the number of weekly predictors. To reduce the dimensionality of my data, I tested a few regularized regression approaches, including Ridge, LASSO, and Elastic Net. These methods shrink the coefficients of less important predictor variables, making the data easier to work with. Figure II (below) displays the result of this shrinking across the regularization methods.

I found that Elastic Net produced the lowest mean-squared error of the three approaches. Since Elastic Net is also a middle-point between LASSO – a more aggressive approach which shrinks some variables to 0 – and Ridge – a more conservative shrinker – I chose to use this method to create my predictions.

| Model | Harris | Trump |

|---|---|---|

| Polls by Week (A) | 51.81 | 50.58 |

| Polls by Proximity (B) | 44.00 | 42.95 |

| GDP Growth (C) | 51.93 | 47.42 |

| Combined (AC) | 51.98 | 47.94 |

| Combined (BC) | 47.96 | 45.19 |

The results of my predictions are displayed in the table above. Model (A) uses the aforementioned week-by-week aggregations. Model (B) adds an explicit adjustment for the polls’ proximity to Election Day. Model (C) does not use polls at all; it is based on Q2 GDP growth, like my forecast from last week. Model (AC) combines the poll-by-week model and GDP growth. Model (BC) weights polls by their proximity to Election Day and also incorporates a measure of GDP growth which is not adjusted for proximity.

My working assumption about voter behavior is that polls will improve with additional proximity to the election, that fundamentals will have a more or less constant level of importance throughout the race, and that – at least for now, with seven weeks to go – fundamentals and polls are roughly evenly matched as predictors. For those reasons, my final prediction for this week is model (BC): 47.96% of the vote share for Vice President Harris and 45.19% for President Trump.

Assessing the Experts

The trade-off between polls and fundamentals is a continual source of tension for professional forecasters, whose models inevitably reflect their creators’ philosophies about voter behavior. In their 2024 forecasts for FiveThirtyEight and the Silver Bulletin, respectively, G. Elliott Morris and Nate Silver both attempt to tread the line between the two.

Polls are the centerpiece of the 2024 Silver Bulletin forecast, though some fundamental measures are incorporated, especially in the early stages of the race. The model uses a combination of a simple average which incorporates a measure of pollster quality and a trendline adjustment which helps reign in wayward state-level polls. Perhaps the most aggressive feature of the model is its “timeline adjustment” which retroactively nudges old polls to account for more recent shifts. This approach, of course, relies on the assumption that polls administered closer to Election Day are substantially more dependable than older polls.

The current FiveThirtyEight model is somewhat more optimistic about the use of fundamentals, though it also decreases their weight as Election Day approaches. The 2024 forecast expands the list of economic variables from six to eleven, including a measure of respondents’ subjective perceptions of the state of the economy (the “Index of Consumer Sentiment”). They argue, based on past elections, particularly 2020, that fundamentals tend to counterbalance bias in the polls. Therefore, fundamentals are incorporated as a baseline to assess poll performance. While this is a compelling possibility, the assumption that this pattern will continue is underdeveloped as written, and makes the model vulnerable to fundamentals and polls trending in the same direction – which could very well happen, especially if the political analysts responsible for maintaining the polls are themselves sensitive to shifts in fundamental conditions.

I am generally suspicious of pollster quality adjustments, which both models use in some fashion. While past performance seems like a reasonable-enough indicator of future accuracy, it could still unfairly punish or reward pollsters for last-minute shifts in voter intentions, or for irresponsible adjustment methods used to nudge the data towards a more popular answer. Other considerations, like “transparency” are even more far-fetched in terms of their predictive value. Though there should be some baseline for poll quality based on widely-accepted randomization procedures and the like, I am inclined to maximize for poll quantity instead, with the hope that an aggregation of truly wide-ranging polls will best approximate the truth.

Of the two models, I tend to prefer the current FiveThirtyEight forecast for the greater range of fundamental variables which it incorporates. To be sure, there is a risk of overfitting with limited historical data, but I am more concerned about the Silver Bulletin model’s vulnerability to short-term pollster hivemind.

References

Morris, G. (2024, June 11). “How 538’s 2024 presidential election forecast works.” FiveThirtyEight. https://abcnews.go.com/538/538s-2024-presidential-election-forecast-works/story?id=110867585

Morris, G. (2024, April 25). “Trump leads in swing-state polls and is tied with Biden nationally.” FiveThirtyEight. https://abcnews.go.com/538/trump-leads-swing-state-polls-tied-biden-nationally/story?id=109506070

Silver, N. (2020, Aug. 12). “How FiveThirtyEight’s 2020 Presidential Forecast Works – And What’s Different Because of COVID-19.” FiveThirtyEight. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/how-fivethirtyeights-2020-presidential-forecast-works-and-whats-different-because-of-covid-19/

Silver, N. (2024, June 26). “2024 presidential election model methodology update.” Silver Bullet. https://www.natesilver.net/p/model-methodology-2024