The Incumbency Advantage(s)

Roughly two-thirds of all presidential elections in the postwar period were won by incumbents. 2024 will not be one such election year, but even without a sitting president on the ticket, the question of incumbency looms larger than ever.

To call incumbency an advantage is a little misleading; especially for a year like this one, it is useful to think of incumbency as a network of often conjoined – but theoretically separable – conditions. There’s name recognition, the ability to direct federal grants, access to the bully pulpit, avoidance of the primary gauntlet, and having already survived one general election, to name a few.

So…who is the incumbent-iest of the 2024 candidates?

Obviously Trump, right? He is a former president, has extensive name-recognition, and was not seriously derailed by his few co-partisan challengers in the primaries.

Or maybe it should be Harris: she’s the sitting Vice President, after all, and she inherited much of Biden’s campaign machinery when he withdrew from consideration. Although…she fell quite a ways short of the nomination in 2020, dropping out early on during primary season, so she hasn’t been thoroughly battle-tested via a national election.

Ultimately, the facets of “incumbency” are not neatly united in either candidate this year, leaving both to awkwardly stake claims to being the real changemaker on the ballot. Rather than using any single measure of incumbency status, the safest option is probably to break it down into its component parts – to the extent that we can identify them – and systematically distribute each one to the best-suited candidate.

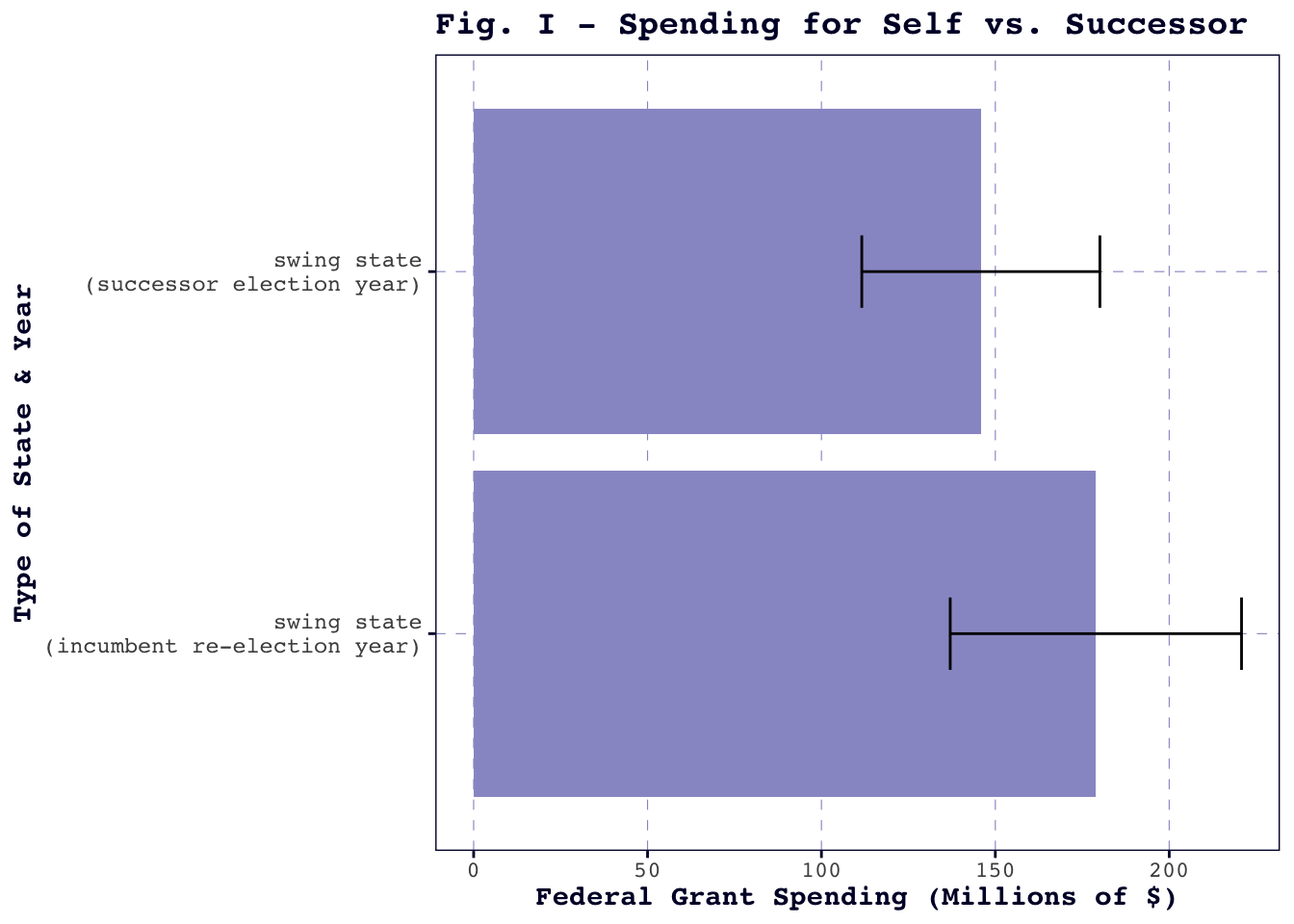

Take, for instance, the allocation of federal grant money – also known as pork – to certain constituencies. The Biden administration has had access to this benefit of office for the last several years. Since, until recently, Biden was running for re-election himself, it seems likely that his spending strategy would fall roughly in line with the pattern depicted in Figure I (below): spending relatively more than he would had Harris been the 2024 candidate from the start.

** Note that these figures are drawn from historical data from Kriner and Greeves (2008) – they are used here to appeal to broad ideas about elected officials’ behavior, not to make specific claims about individual politicians or recent events. **

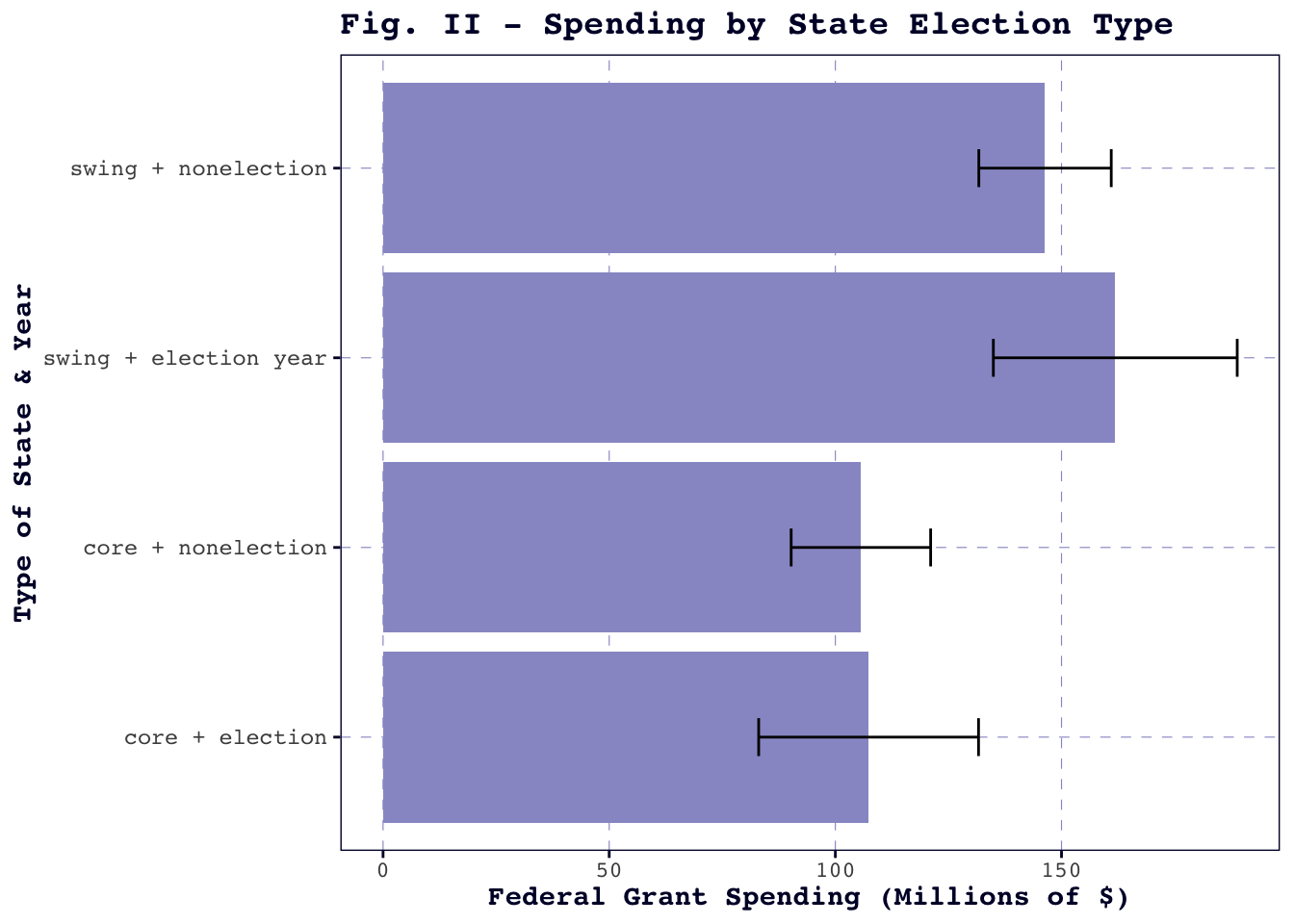

Thus, the last-minute switch-out allows Harris to enjoy at least one of the benefits of being a straightforward incumbent. However, the picture is not entirely as simple as it seems. In Figure II (above), we see that incumbents tend to allocate pork in greater quantities to swing states, especially during election years. This means that any strategic spending by Biden is vulnerable to slight changes in the electoral map with Harris as the Democratic nominee; though overall federal grant spending might have declined had Biden never sought re-election, the administration might have been able to spend more strategically had the Harris campaign started earlier.

As I move into this week’s predictive models, which do not come close to capturing all of these complexities, it is worthwhile to keep these limitations in mind. Determining who gets to be an incumbent, and to what degree, may be the make-or-break question for forecasters during this strange, abbreviated election cycle.

Is it Time for Change?

Alan Abramowitz’s Time for Change model uses just three explanatory variables – incumbency status, the president’s June approval rating, and GDP growth during Q2 of the election year – to predict the incumbent party’s vote share. The model’s basic philosophy is that voters experience incumbent fatigue at predictable intervals, and that this ebb and flow largely determines presidential election results.

With 2020 omitted from the training data, since Abramowitz implemented a COVID-specific model, and Harris categorized as a non-incumbent, Time for Change predicts a Democratic two-party vote share of 46.67%. The table below expands on this finding – notably, the 50% mark falls within the selected confidence interval, so the model cannot be said to predict a popular vote winner at an 80% confidence level.

| Prediction | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Adjusted R-squared |

|---|---|---|---|

| 46.67 | 42.05 | 51.29 | 0.67 |

The table also indicates that the model, despite having just three components, explains a respectable two-thirds of the observed variation in historical incumbent party vote share.

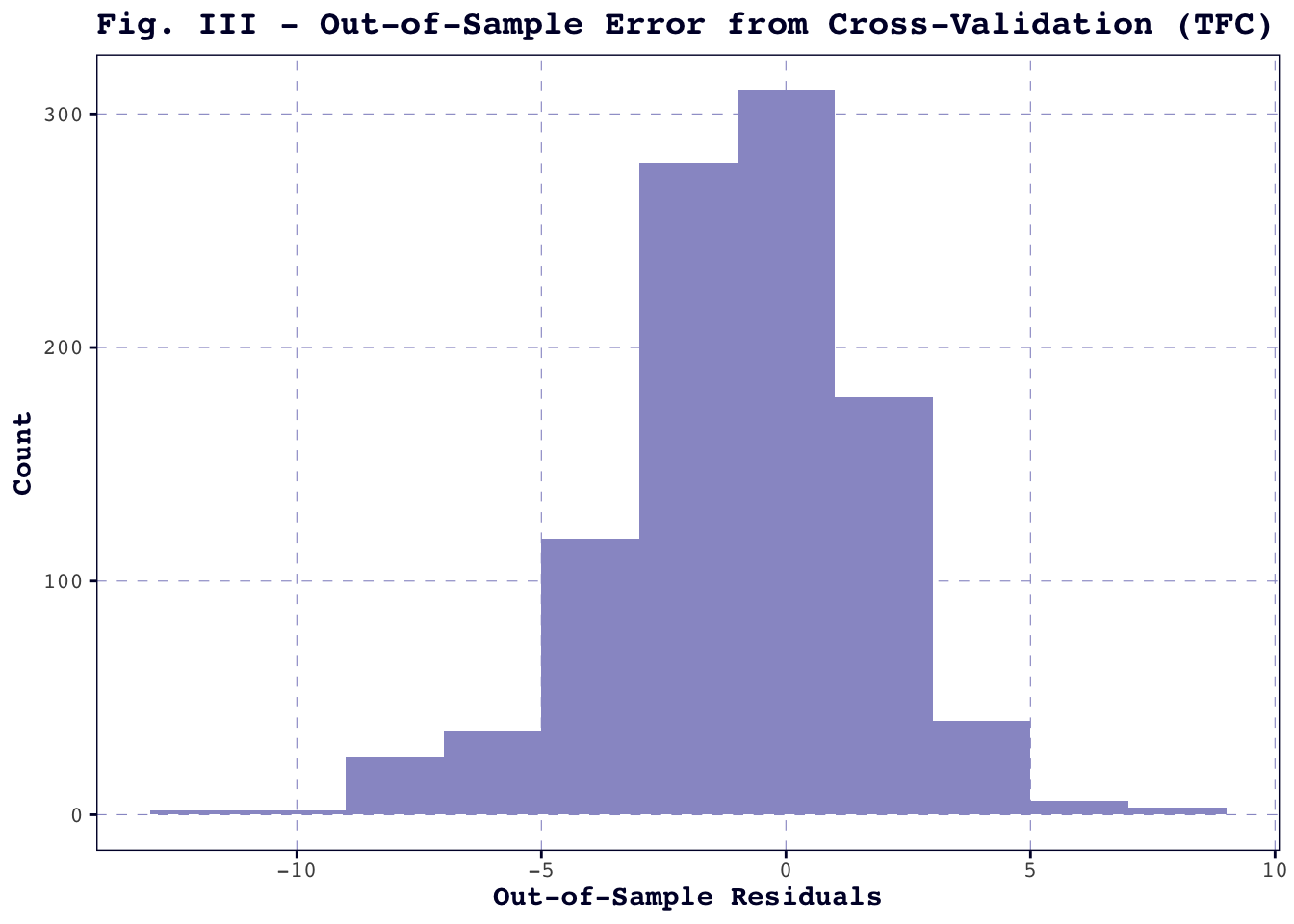

I also performed one thousand runs of a cross-validation procedure, randomly selecting half of the election years in my dataset to test the model each time, and found that the mean of the absolute value of the out-of-sample residuals was equal to approximately 2.1. Given that the vote share variable has a range of almost 20 points, this, too, seems like a positive indication of model quality. Figure III (below) displays the distribution of out-of-sample errors; they are approximately normal, which suggests that the model overestimates incumbent party performance about as often as it underestimates.

How About Even More Change?

Time for Change is altogether an impressive model; given the looming threat of overfitting, its simplicity is particularly admirable. In this section, I propose three tweaks to Time for Change, which seek to accommodate some of the quirks of the current election season while retaining the simple construction of the original.

First, I replaced Q2 GDP growth – a measure of factual economic performance – with subjective impressions of the Q2 economy. This new measure is drawn from the University of Michigan’s Index of Consumer Sentiment, and is meant to account for voters who still feel the pinch of inflation despite recent economic recoveries.

Next, I used averaged poll aggregations from 7 weeks before the election instead of June approval ratings. Not only do June approval ratings have Biden, rather than Harris, as their subject, but even if I were to input Harris’s June approval ratings, respondents were not evaluating her as a presidential candidate at that time. Neither of those June measures seem appropriate. Admittedly, it remains to be seen whether the 7-week polls still reflect the echoes of a “Harris honeymoon” that will fade by Election Day.

Finally, I substituted an indicator for whether a candidate was a member of the previous administration for Abramowitz’s incumbency variable. If Time for Change gave Harris too little credit for her proximity to Biden, this change will start close the gap.

The results of my revised predictions are below: Time for More Change makes all three changes, while the other models keep all but one of Abramowitz’s variables (so “Index of Consumer Sentiment” uses consumer sentiment, June approval, and incumbency).

| Model | Prediction | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Adjusted R-squared | Average Absolute Value of Out-of-Sample Residuals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time for Change | 46.67 | 42.05 | 51.29 | 0.67 | 2.09 |

| Time for More Change | 50.69 | 47.15 | 54.22 | 0.77 | 1.58 |

| Index of Consumer Sentiment | 47.06 | 42.63 | 51.49 | 0.67 | 2.03 |

| Poll Average at 7 Weeks To Election | 52.25 | 48.18 | 56.31 | 0.70 | 1.69 |

| Previous Administration | 45.50 | 40.85 | 50.15 | 0.65 | 1.99 |

This Week’s Prediction

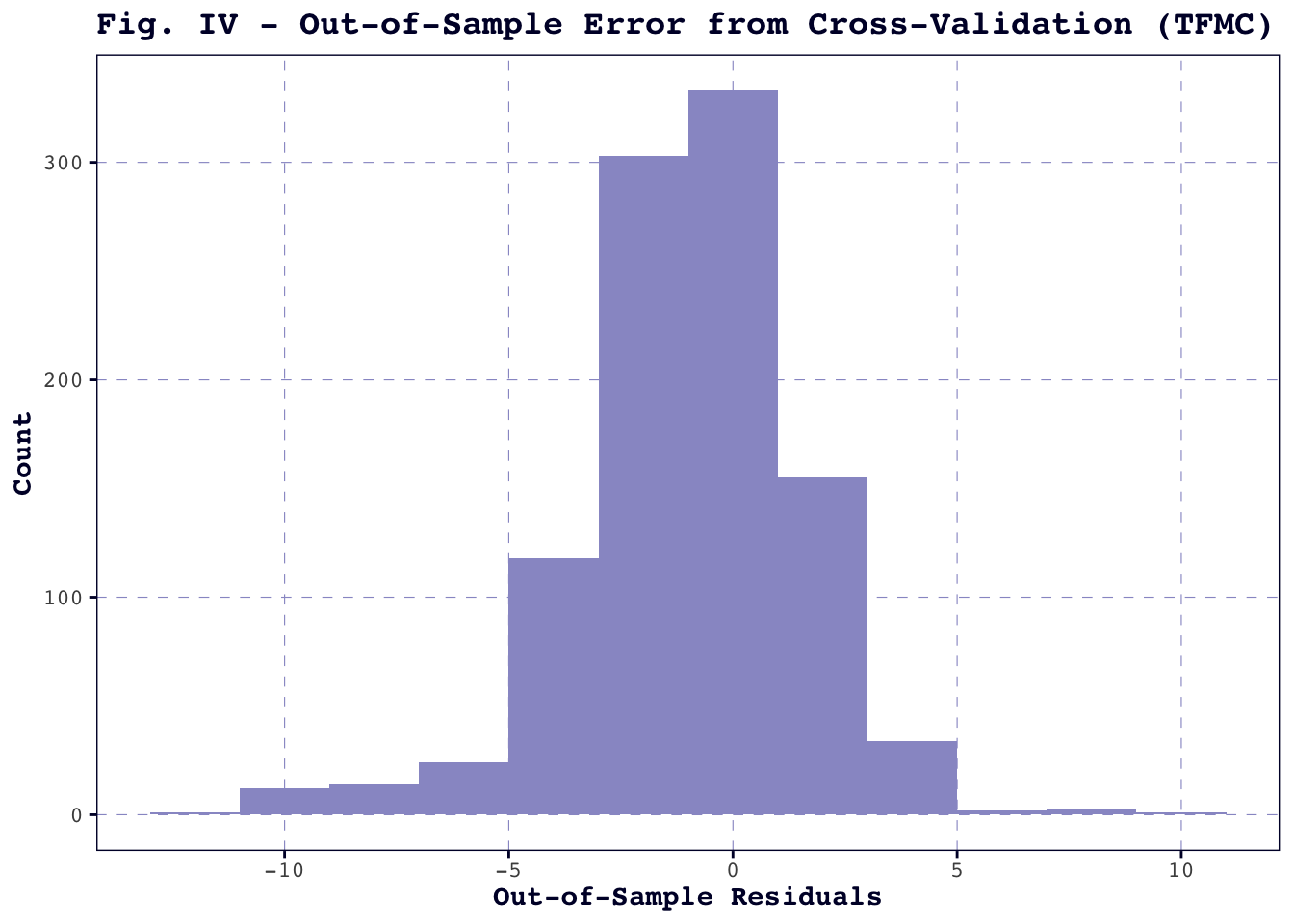

The completely revamped Time for More Change model performed the highest on the selected measures of in-sample and out-of-sample fit (adjusted R-squared and the average absolute value of out-of-sample errors, respectively). I also produced a visual representation of the cross-validation errors (below, Figure IV): the distribution again appears to be near-normal.

Since Time for More Change also addresses my main substantive concerns with the Abramowitz model, it is my preferred model for this week. Whether I have given too much weight to Harris’s role in the Biden administration remains to be seen. For now, I will leave you with the Time for More Change prediction of a 50.69% Harris two-party popular vote share.

Until next time!