Demographics & Voter Files

However sophisticated their statistical techniques may be, even the greatest election forecasters can be humbled by hard-to-track changes in voter turnout. News reports unsurprisingly focus on the salacious headline story of voter behavior – who undecideds are inclined to vote for – and place less emphasis on the underlying issue of voter turnout. But of course, polls start to lose their sheen if they appear to be a poor proxy for the intentions of those who will ultimately cast their ballots.

Though Census data is an invaluable resource in analyst’s efforts to reconcile noisy, overinclusive data with recognized demographic patterns, it does not provide the full picture. Not only can the Census itself be overinclusive – non-citizens, among other non-voting residents, may be counted – but since it is updated just every ten years, its accuracy is continually declining. In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, which shifted large numbers of workers into long-term remote work positions and gave some the opportunity to move across district and state lines, we should be particularly cautious about interpreting Census data as convincing evidence of who (still) lives where.

Voter files – though not a panacea by any means – help bridge some of these shortcomings. These state records provide political campaigns with the invaluable opportunity to target voters on a microscopic level, and allow forecasters to seek a second opinion about a population’s demographic characteristics, and by extension its likely turnout.

To kick off this week’s blog, I took a brief look at voter files from my home state of Delaware.

I first conducted a simple linear regression to see which demographic variables seemed to be the best predictors of turnout. The summarized output, below, interestingly suggests that race and party registration have little observable impact on voter turnout.

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = svi_vote_all_general_pres_pct ~ sii_age_range +

## sii_gender + sii_race + svi_party_registration + sii_education_level +

## sii_homeowner, data = vf_de)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -95.581 -24.629 9.771 24.059 85.261

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 30.7598 17.7714 1.731 0.083518 .

## sii_age_rangeB 17.3342 1.5268 11.353 < 2e-16 ***

## sii_age_rangeC 22.6238 1.5491 14.605 < 2e-16 ***

## sii_age_rangeD 31.0418 1.3985 22.197 < 2e-16 ***

## sii_age_rangeE 36.6073 1.5246 24.011 < 2e-16 ***

## sii_age_rangeF 39.2695 1.6560 23.714 < 2e-16 ***

## sii_genderM -4.2739 0.8270 -5.168 2.43e-07 ***

## sii_genderU -7.8137 2.5018 -3.123 0.001796 **

## sii_raceB 2.1753 3.1272 0.696 0.486697

## sii_raceH -1.9438 3.5801 -0.543 0.587172

## sii_raceN 2.8391 16.0844 0.177 0.859896

## sii_raceO -15.8210 24.8782 -0.636 0.524835

## sii_raceU -5.1535 6.9498 -0.742 0.458396

## sii_raceW 4.2272 2.9979 1.410 0.158565

## svi_party_registrationD 10.1942 17.4745 0.583 0.559657

## svi_party_registrationG 10.0633 21.0731 0.478 0.632989

## svi_party_registrationL 13.2126 19.5199 0.677 0.498504

## svi_party_registrationR 9.1524 17.4831 0.524 0.600641

## svi_party_registrationT -6.5079 39.0859 -0.167 0.867765

## svi_party_registrationU 0.8759 17.4808 0.050 0.960041

## svi_party_registrationW -24.1822 24.7141 -0.978 0.327872

## sii_education_levelB 11.0025 0.9875 11.142 < 2e-16 ***

## sii_education_levelC 12.1717 1.3908 8.751 < 2e-16 ***

## sii_education_levelD 8.7111 4.7995 1.815 0.069565 .

## sii_education_levelE 9.5529 1.7538 5.447 5.28e-08 ***

## sii_homeownerR -7.4689 1.9879 -3.757 0.000173 ***

## sii_homeownerU -5.8447 0.9846 -5.936 3.05e-09 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 34.9 on 7423 degrees of freedom

## (3180 observations deleted due to missingness)

## Multiple R-squared: 0.1814, Adjusted R-squared: 0.1785

## F-statistic: 63.25 on 26 and 7423 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

That party registration seems to play such a small role is particularly counterintuitive since Delaware is a reliably blue state, in which Republican voters might conceivably be less motivated to vote in non-competitive federal races. Further research is needed to draw any detailed conclusions, but perhaps bipartisan interest in more competitive down-ballot races is driving this distribution.

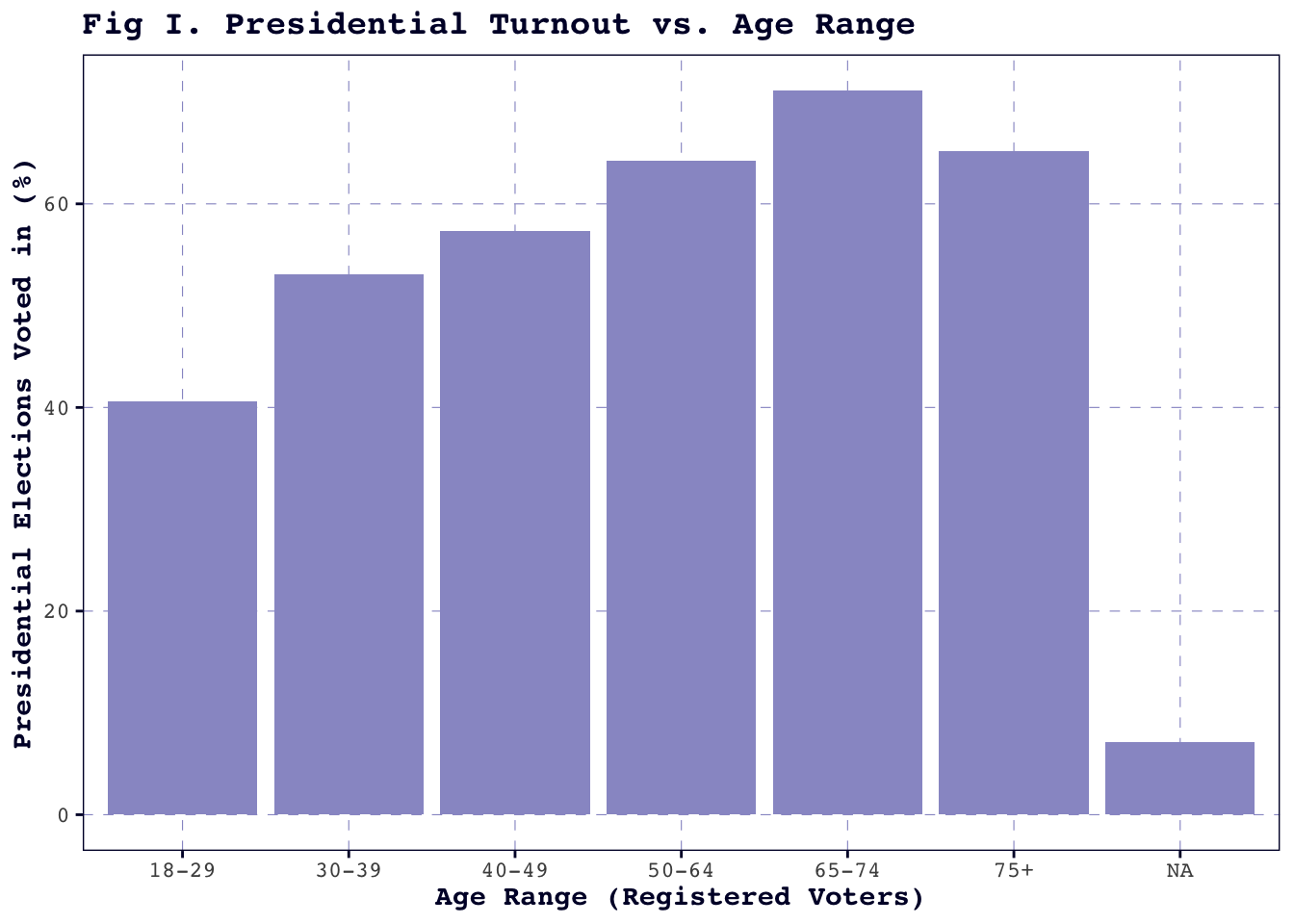

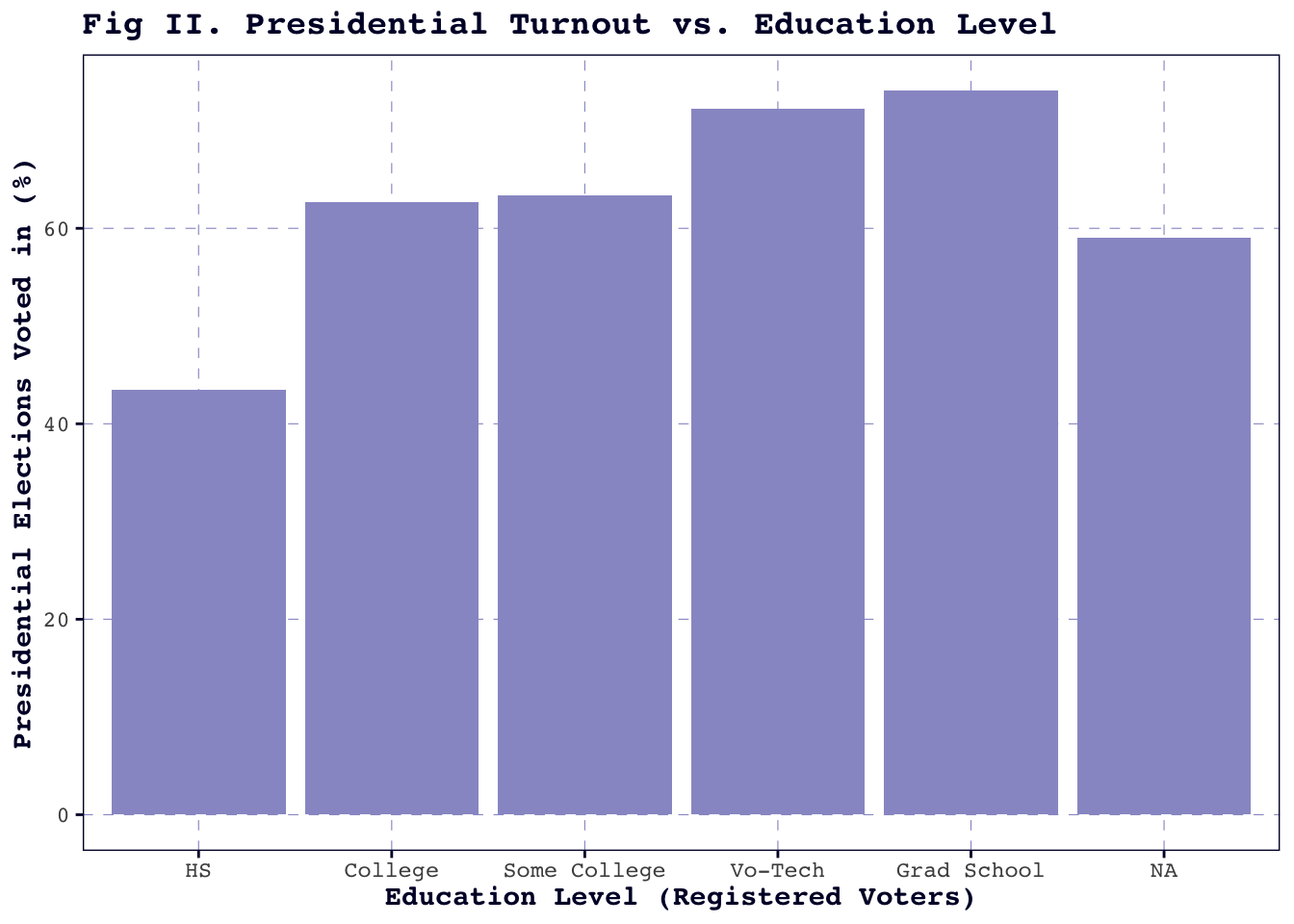

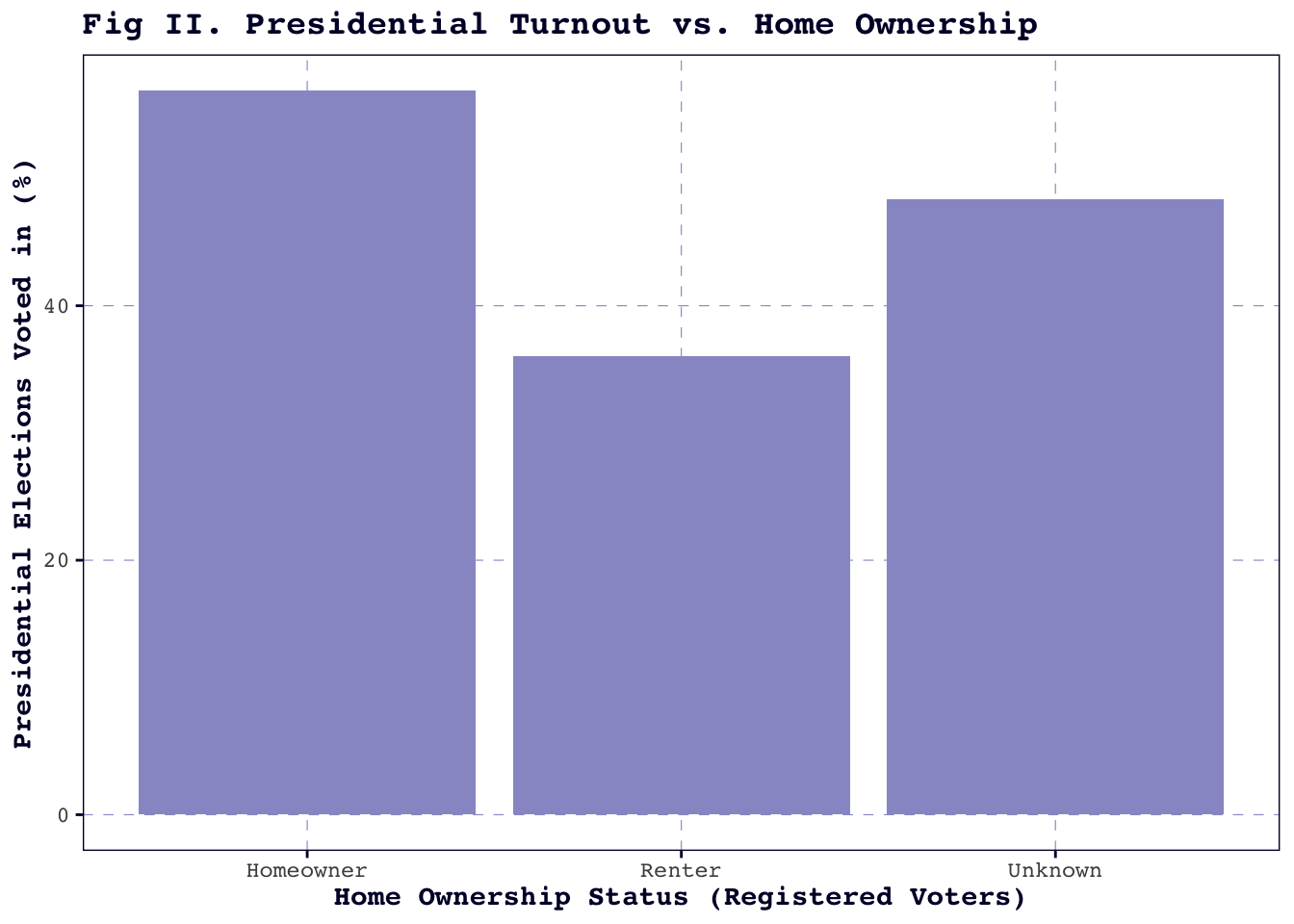

Figures I-III, below, summarize voter turnout rates across the variables determined to be most significant by the regression model: age, education level, and home ownership. In this regard, Delaware seems to be in lock-step with the conventional wisdom that older, wealthier, and more highly-educated individuals are more likely to vote. Not only do these groups often have an easier time shouldering the opportunity costs of voting, but they may also have distinctive policy interests that motivate them to participate. For instance, retirees may find it easier to take time out of their days to go to the polls, and they may also be impassioned about defending Social Security.

This Week’s Prediction

This week’s model is an elaboration on the Time for More Change approach I proposed in last week’s blog. Time for More Change borrows its basic framework from Abramowitz’s Time for Change model, with a few tweaks made to account for the specific conditions of the 2024 race, namely, swapping out Biden’s June approval for Harris’s support in recent poll averages, incorporating the Index of Consumer Sentiment to acknowledge feelings – not just facts – about the state of the economy, and using a binary variable to indicate participation in the previous administration.

Time for More Change predicts a Harris two-party popular vote share of 50.69%, with an upper bound of 54.22% and a lower bound of 47.15% at the 80% confidence level. This reflects the popular consensus that 2024 will be an exceptionally close contest, although even a very poor model could have stumbled into a prediction around the 50% mark.

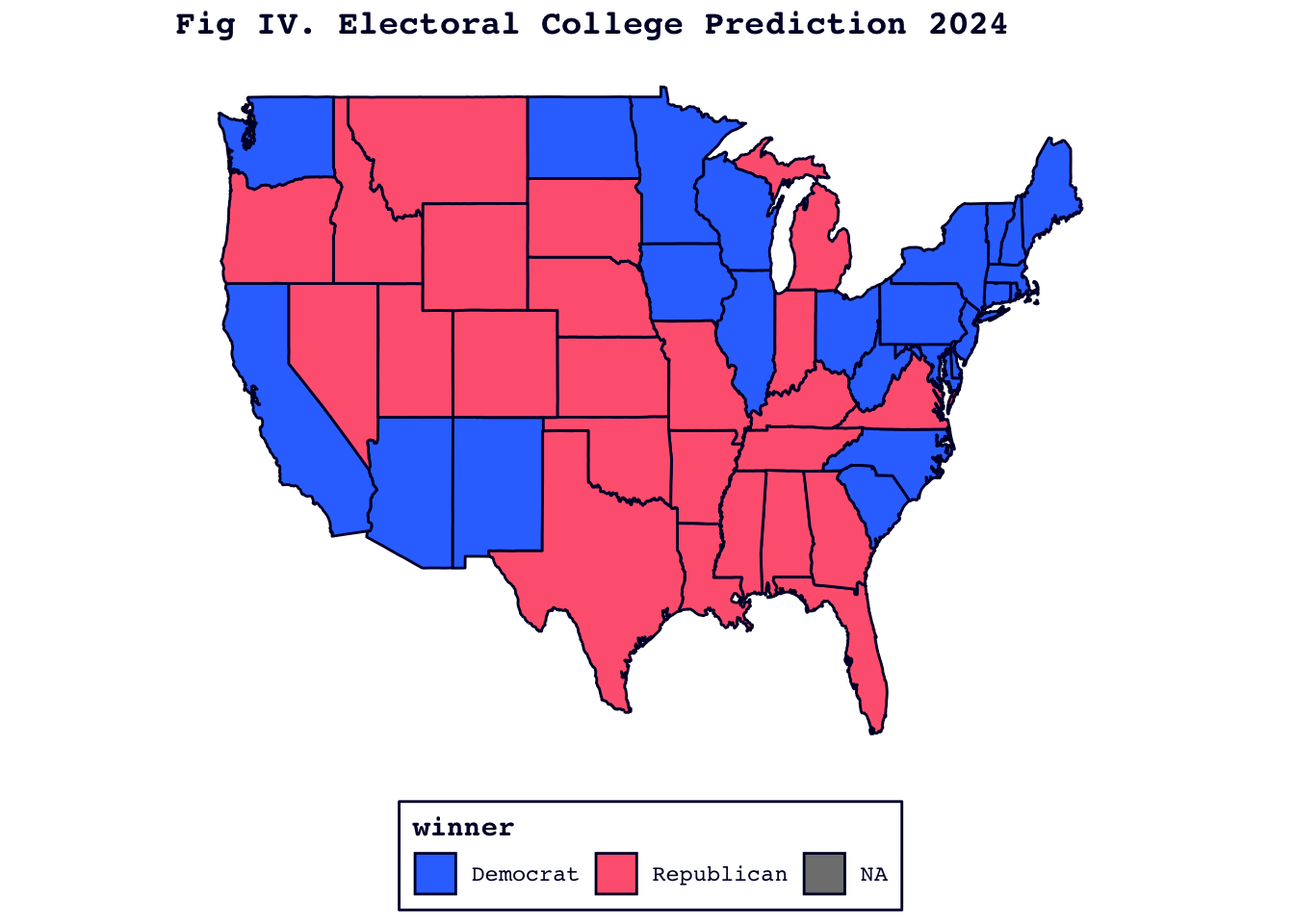

The real stress test for Time for More Change comes from the electoral college prediction, which I have added for this week.

The most pressing issue I faced in constructing the electoral college extension of Time for More Change – besides some disastrous human error that had me temporarily predicting a blue Texas and a red Massachusetts – was accounting for the vast majority of the states which lack current polling data. I used Biden’s 2020 vote share by state and the most recent national polling average to fill in the gaps in these cases, but it is by no means a perfect proxy for polls. Fortunately, all of the major swing states for 2024 have state-level polling.

Time For Change predicts that Harris will receive 287 electoral college votes, which would give her the presidency. While this estimate in itself is not out of the realm of possibility (give or take a few votes from Maine and Nebraska’s congressional districts, since their proportional systems are not yet incorporated in this model), it does produce a slightly sketchy map.

In Figure IV, below, the model has Oregon and Virginia swinging toward the Republicans and Ohio, West Virginia, North Dakota, and South Carolina breaking for Harris. It is difficult to evaluate the model’s prediction of the swing states – even though we have more recent polling in those cases, they are genuinely up for grabs, so possible errors in their predicted electoral college vote are not as obvious as the improbable North Dakota guess.

There is plenty more to be done with this model – its forecasting uncertainty is poorly defined, it is essentially blind to campaign factors and vulnerable to unrepresentative polls, and the Time for Change approach’s focus on incumbent party vote share means that it says very little about Trump’s viability as a candidate.

See you next week!