Presidential Campaigns: America’s Multimillion Dollar Myth?

In a year like this one, presidential campaigns can seem inescapable. The candidates’ likenesses are plastered on television screens and websites. Droves of canvassers go door-to-door, vying for a dwindling supply of undecided voters. Even silly, apolitical internet memes are no longer safe from tech-savvy campaign staffers.

Campaigning on such a ludicrous scale, mind you, is far from cheap. As of October 13th, 2024, the Federal Election Commission reports that the Harris campaign has disbursed just over 445 million dollars and that the Trump campaign has disbursed almost 180 million dollars. With both major campaigns putting so much skin in the game, one might reasonably expect the persuasive benefits of campaigning to be enormous, but social scientific research is less optimistic.

In their 2007 study, Huber and Arceneaux find that exposure to one-sided campaign advertisements may persuade some voters, though they do not find sufficient evidence to argue that ads effectively mobilize supporters or inform the previously unaware. This finding is further tempered by a later experiment conducted by Gerber et al. in collaboration with Rick Perry’s 2010 gubernatorial campaign. The authors suggest that the legitimate persuasive effects documented by researchers like Huber and Arceneaux are liable to fade shortly after exposure.

While these conclusions do not in and of themselves imply that campaigns are a waste of money, they do cast doubt on the wisdom of spending big on advertisements early on.

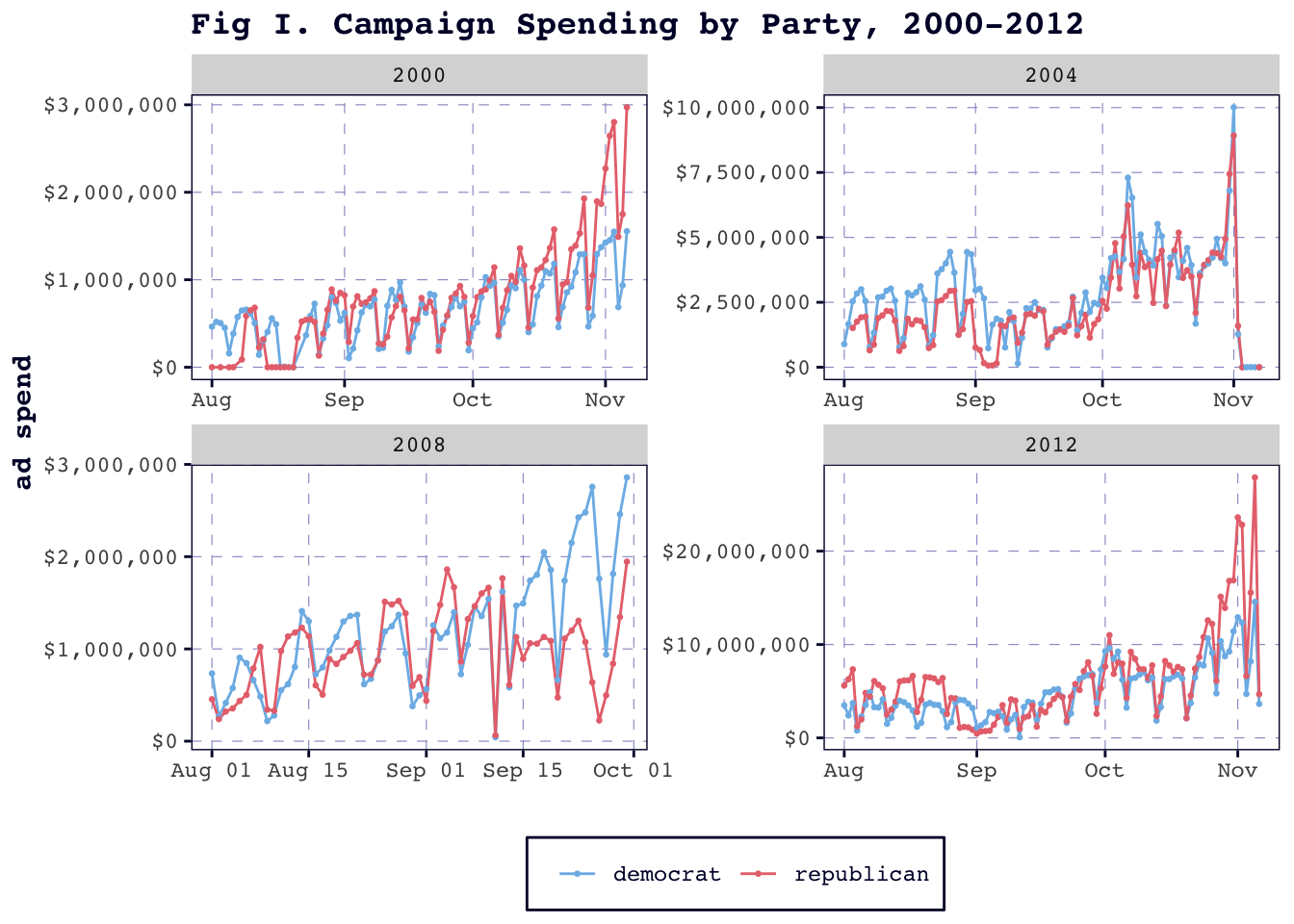

Nevertheless, as Figure I (below) demonstrates, candidates have been dipping into their funds months ahead of Election Day for quite some time – certainly in each of the first four elections of this century.

These graphs, which show the opposing candidates largely in lockstep with one another, suggest that the campaigns’ strategy has more to do with keeping their head above water than with changing hearts and minds. Interestingly, the Bush campaign in 2000 and the Obama campaign in 2008 seem to move slightly ahead of their competitors in terms of spending towards the end of the race, which both won in their respective years. However, it is unclear whether that additional spending made a difference in the final result, or if instead the campaigns were responding to external conditions which convinced them – and their respective opponents – that the race was increasingly in their favor.

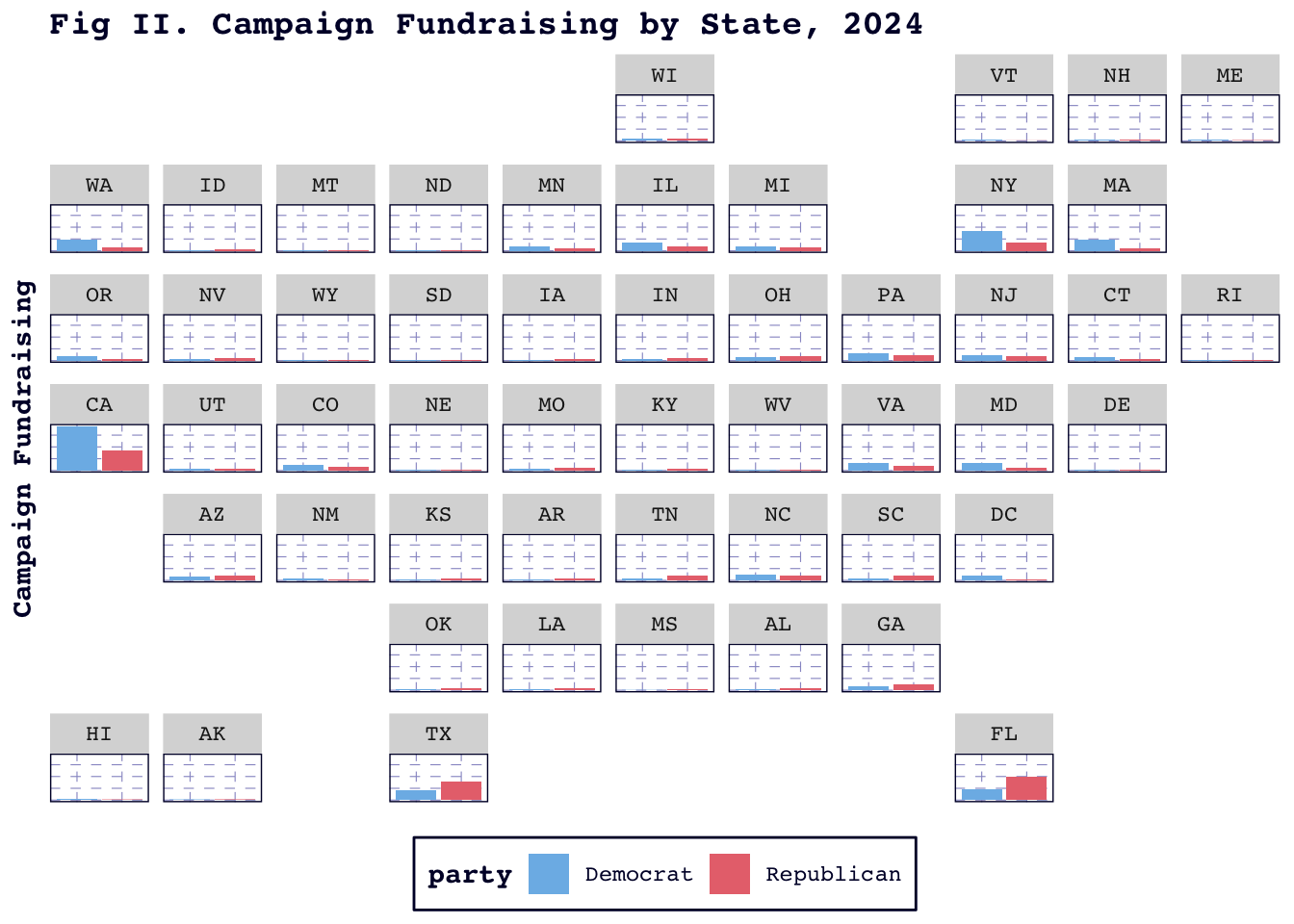

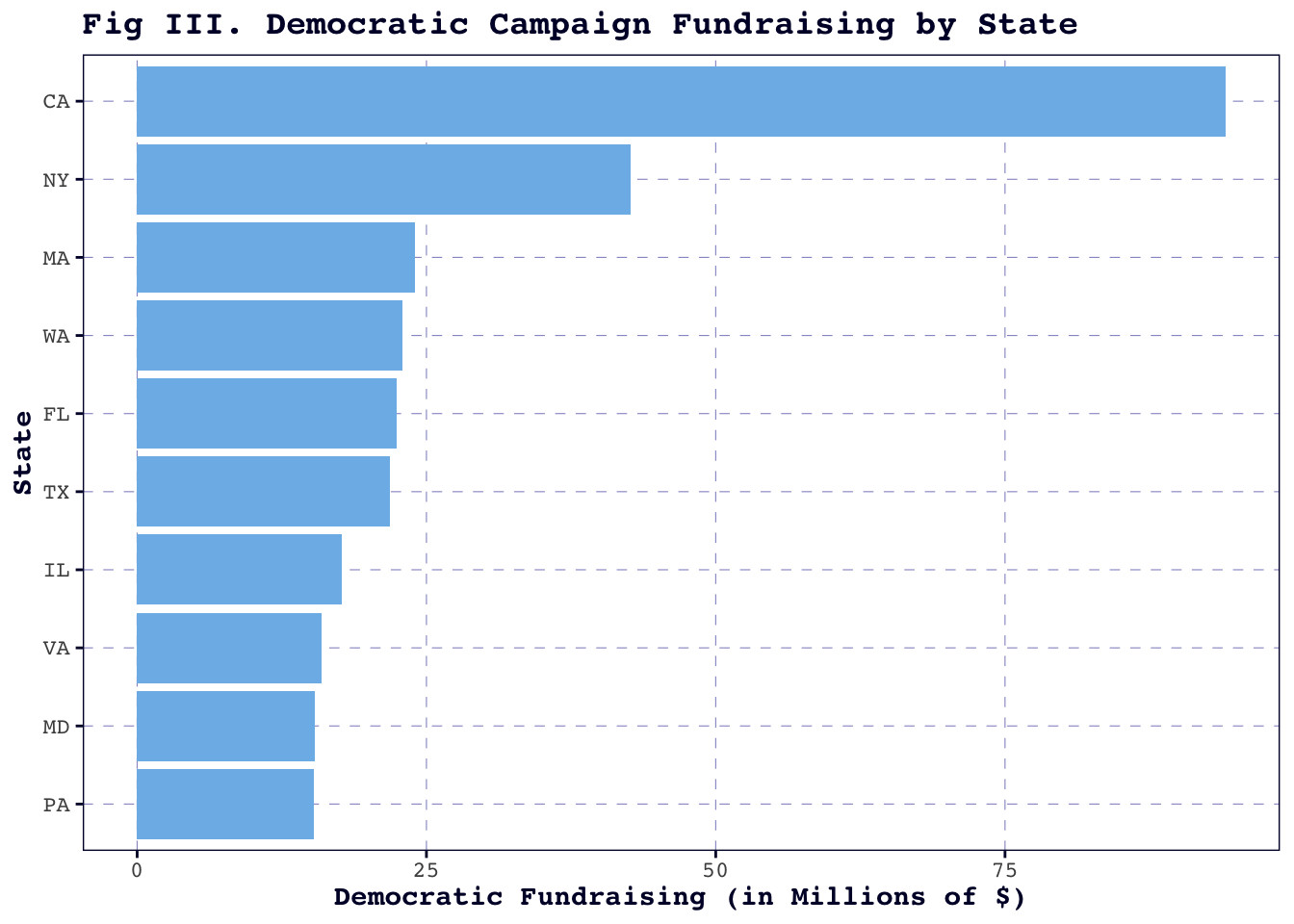

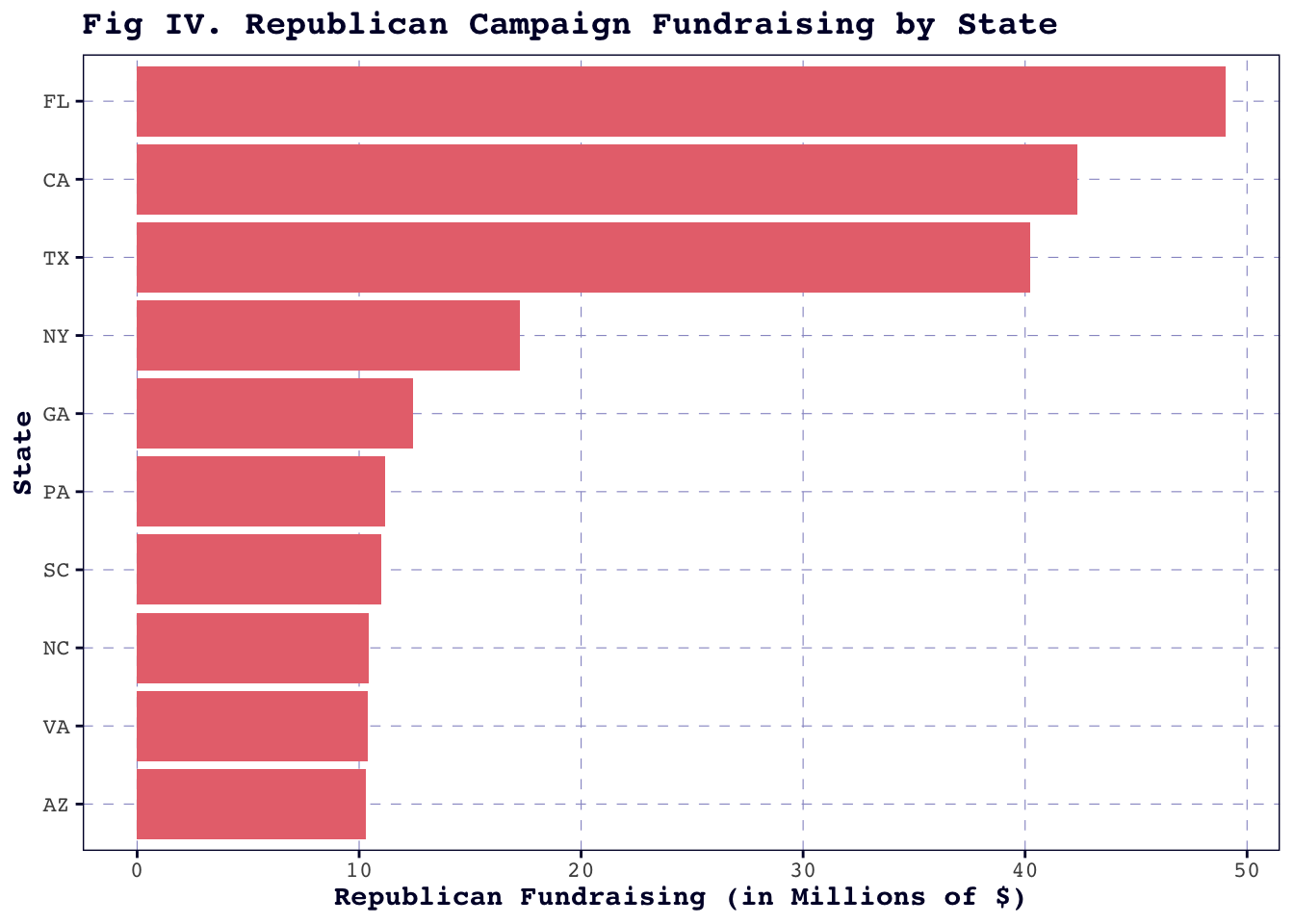

Detailed spending patterns in 2024 are not yet captured in these datasets. Instead, Figure II (below) breaks down the major party candidates’ fundraising by state; while some high-profile battlegrounds, like Pennsylvania, do account for a solid share of overall fundraising, reliable voters like California, Texas, Florida, and New York unsurprisingly overshadow them.

Figures III-IV, below, bring the fundraising trends for each party into clearer focus.

Overall, the Harris campaign seems to be outperforming Trump in the fundraising arena, which could perhaps buck the trend of highly balanced presidential campaigns seen in earlier 21st century races. However, both campaigns do have substantial funds, and it remains to be seen how strategically they will deploy their resources. On the other hand, if we take these results as a rough indicator of enthusiasm at the state level, these visualizations could instead be a good sign for the Trump campaign, since more battleground states appear in the Republican top 10. This, though, assumes that enthusiasm among donors – who are likely politically engaged partisans – translates into increased support among persuadable swing voters, which may very well not be the case.

This Week’s Prediction

This week’s prediction retains much of the basic structure from last week. The dependent variables are now incumbency status, the Q2 Index of Consumer Sentiment, the national polling average with four weeks to Election Day, and lagged vote share. This model yields a prediction of 53.44% for Harris’s two-party popular vote share – somewhat higher than last week.

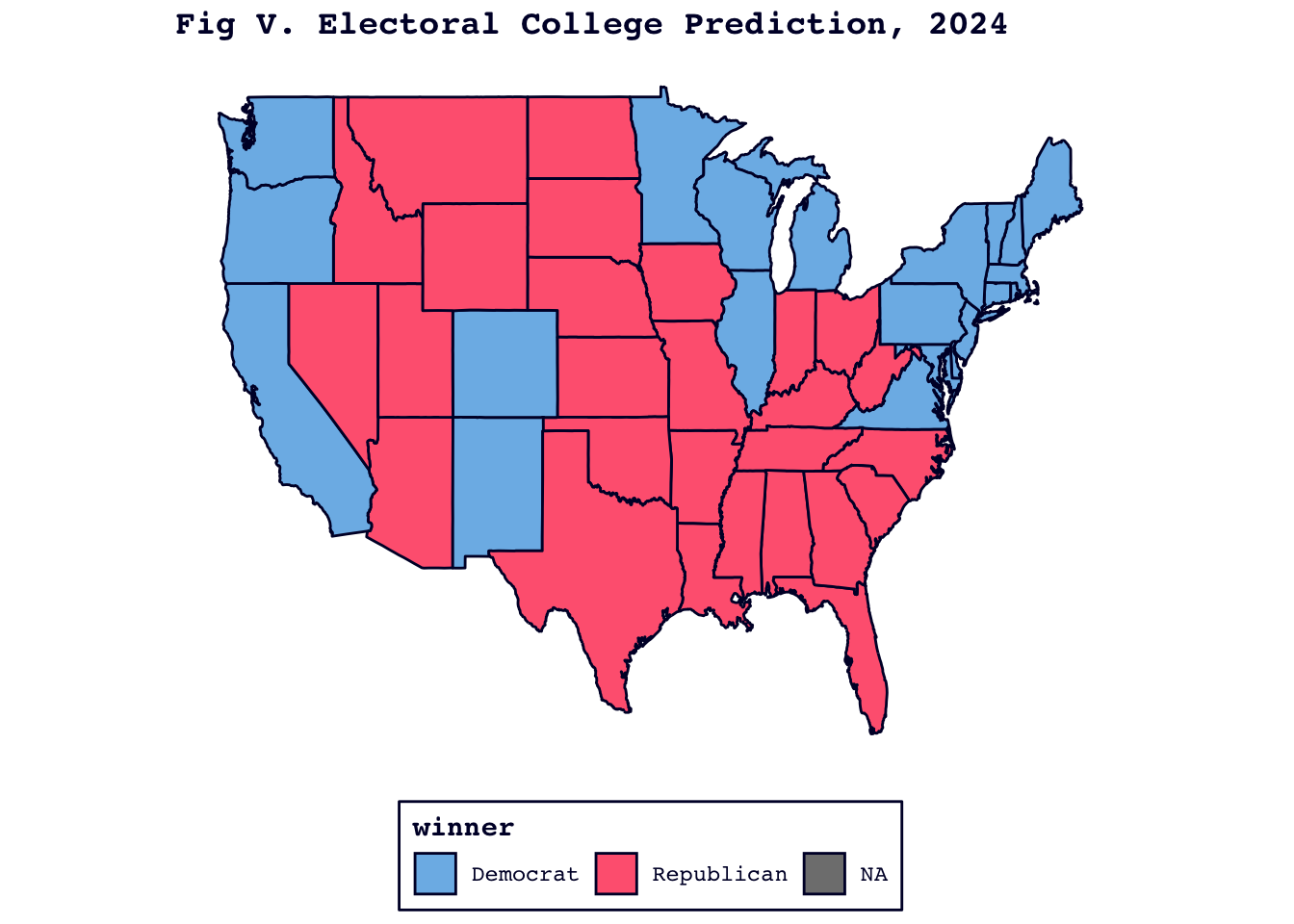

More exciting by far, however, is the updated electoral college prediction, which (drumroll, please!) now has Ohio, West Virginia, and South Carolina breaking for Trump and no longer produces an absurd, negative estimate for Wyoming. Two changes allowed me to make this much more sensible model – though of course its ability to predict the swing states is still up in the air. First, I took TF Matthew’s suggestion to impute missing 2024 state polling by applying a penalty term equivalent to the state polls’ deviation from the final state vote share in 2020 to the current national polling average. Then, I recalibrated the state vote lags, which had become wildly inaccurate in one of the merging steps.

The result (in Figure V, below) is a model which predicts that Harris will hang onto the Blue Wall but fall short in the other battleground states, narrowly losing the electoral college with 267 votes. However, DC’s three electoral votes, which are likely not in jeopardy for the Democrats, would be enough to carry her to the 270-vote threshold in this scenario.

With this visual sanity check now completed, I am excited to make more substantive changes to the model in the weeks to come. See you next week!

Correction: An earlier version of this post incorrectly stated that Figures II-IV depict trends in campaign spending. In fact, the variable of interest is campaign fundraising.

References

Alan S Gerber, James G Gimpel, Donald P Green, and Daron R Shaw. “How large and long-lasting are the persuasive effects of televised campaign ads? Results from a randomized field experiment.” American Political Science Review, 105(01):135–150, 2011. https://hollis.harvard.edu/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=TN_cdi_proquest_miscellaneous_881466543&context=PC&vid=HVD2&search_scope=everything&tab=everything&lang=en_US.

Federal Election Commission. “US President.” 2024. https://www.fec.gov/data/elections/president/2024/.

Gregory A Huber and Kevin Arceneaux. “Identifying the persuasive effects of presidential advertising.” American Journal of Political Science, 51(4):957–977, 2007. https://hollis.harvard.edu/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=TN_cdi_proquest_miscellaneous_59786011&context=PC&vid=HVD2&search_scope=everything&tab=everything&lang=en_US.