The Ground Game

Knocking on doors may seem a little old-fashioned, but the tradition of the ground game is alive and well in modern presidential politics. In fact, the famously cutting-edge Obama campaign is often credited with the return to one-to-one voter outreach.

What follows is a brief look at recent electoral history. By showing how past candidates have navigated this aspect of campaign infrastructure, I hope to sketch out a very general baseline for how the 2024 candidates might be approaching this race.

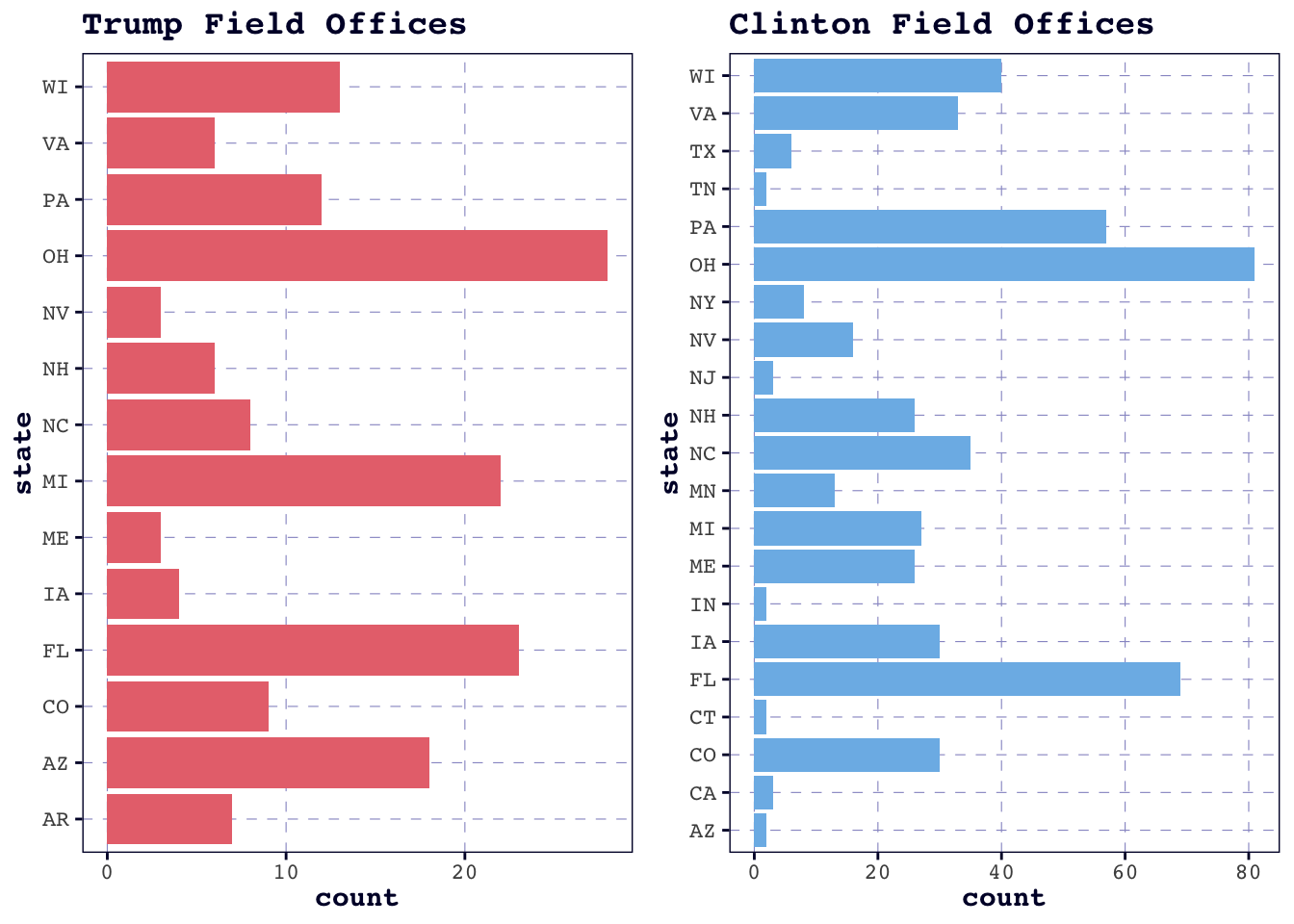

The first trend that seems to emerge is that campaigns heavily focus their field office resources in swing states. In the figure below, there is broad overlap between the candidates’ choice of locations, with both Trump and Clinton seeming more invested in states which, in 2016, seemed at least somewhat purple. The Clinton campaign appears to have been more willing to distribute a few field offices to non-competitive states, although this could also be a reflection of its larger ground game infrastructure overall. In both plots, states with only one field office were removed for improved legibility.

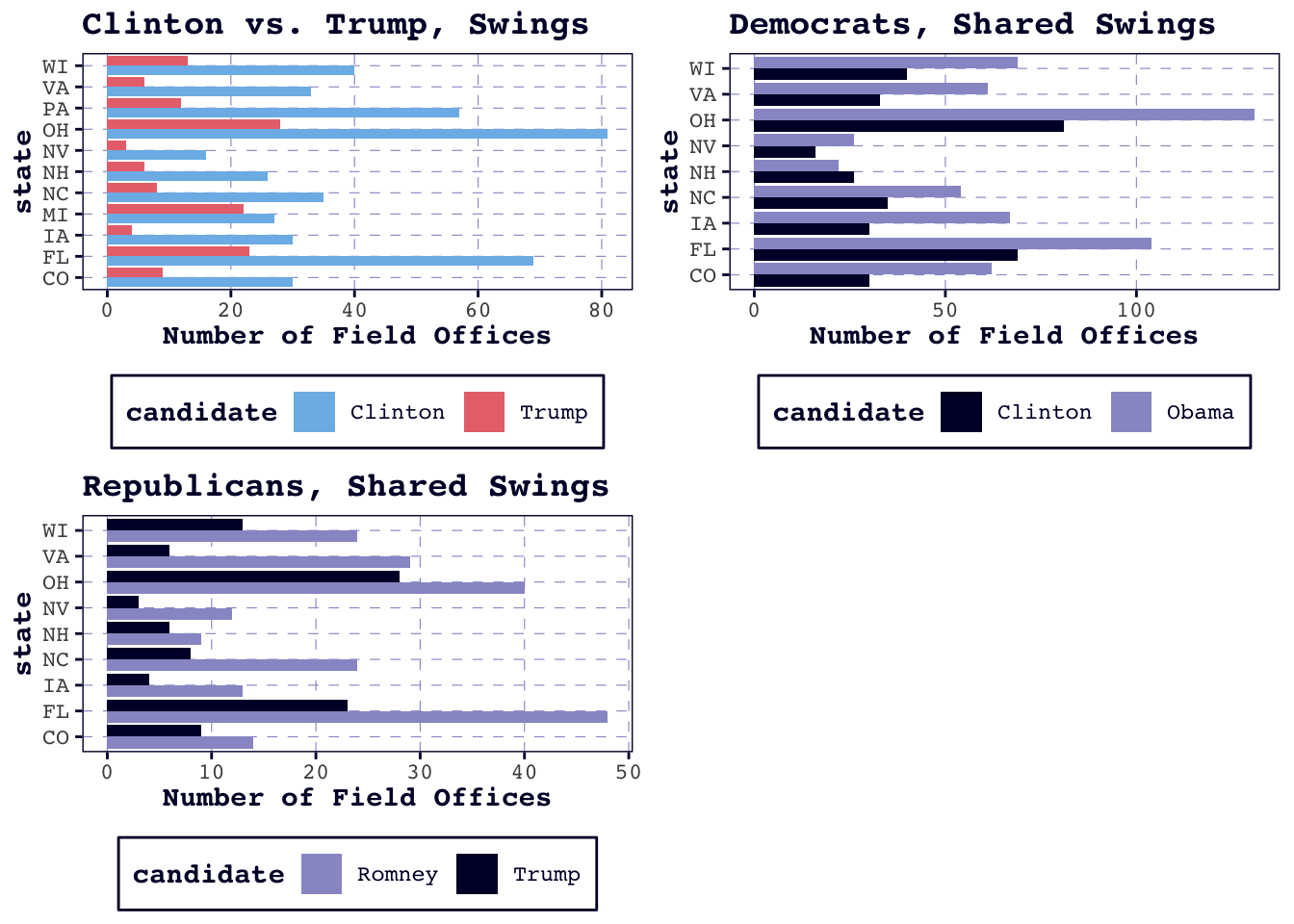

The next set of plots, below, compares the 2016 candidates to one another, and to their co-partisan predecessors in the 2012 contest.

Notably, Clinton had more field offices than Trump in all of the swing states, including the Blue Wall states where she was favored to win (though of course she did not). Interestingly, her ground game advantage seems to be bigger in then-swing states like Florida and Ohio which have now moved to the Republican camp; perhaps a sign that her campaign was overambitious in red-trending states, at the expense of places like Wisconsin and Michigan.

The following two plots reinforce the idea that 2012 was an exceptional year in terms of the ground game: both Romney and Obama handily outperform Trump and Clinton, respectively, in terms of the quantity of field offices they established in swing states. (Note that “shared swings” refer to states designated as swing states in both 2012 and 2016.) Since similar data from 2024 is not yet available, it remains to be seen whether 2024 has the momentum of the 2012 cycle, or if comparing overall ground game resources will be as misleading as Clinton’s apparent lead over Trump in 2016.

Presidential campaigns, of course, are not what they were in 2012, or even 2016. The irregularity of the 2020 election, especially with regard to in-person outreach, may further hamper our ability to find trends in the recent past. New patterns of social media usage, increased absentee voting, and new strategies – like the Trump campaign’s decision to outsource much of its door-knocking efforts to paid canvassers – are all strong contenders shake up this cycle’s ground game.

This Week’s Prediction

This week’s model is a continuation of the last few weeks – its predictions are functionally the same as before (despite updating the polling input and fixing a coding error in the imputation process for the states which lack polling data for 2024), but I have started to quantify some of the uncertainty built into the model.

This week, my model predicts that Harris will receive 53.54% of the two-party popular vote share, a very modest increase from last week. The national popular vote regression has an adjusted R-squared of approximately 0.77, meaning that around 77% of the variation in Democratic vote share captured in the training data is explained by the independent variables: Q2 Index of Consumer Sentiment, the national FiveThirtyEight polling average at three weeks until Election Day, incumbency status, and the lagged popular two-party vote share for the Democratic party.

Clearly, there are other factors at play – including, possibly, candidate features like personality traits which may be harder to quantify than economic variables – which make this model imperfect, but an adjusted R-squared of 0.77 is, in my view, a mildly positive sign. After all, it is higher than the calculated statistic for Abramowitz’s Time for Change model, which is the inspiration for this framework, and extremely high R-squareds can indicate overfitting, which dilutes predictive power.

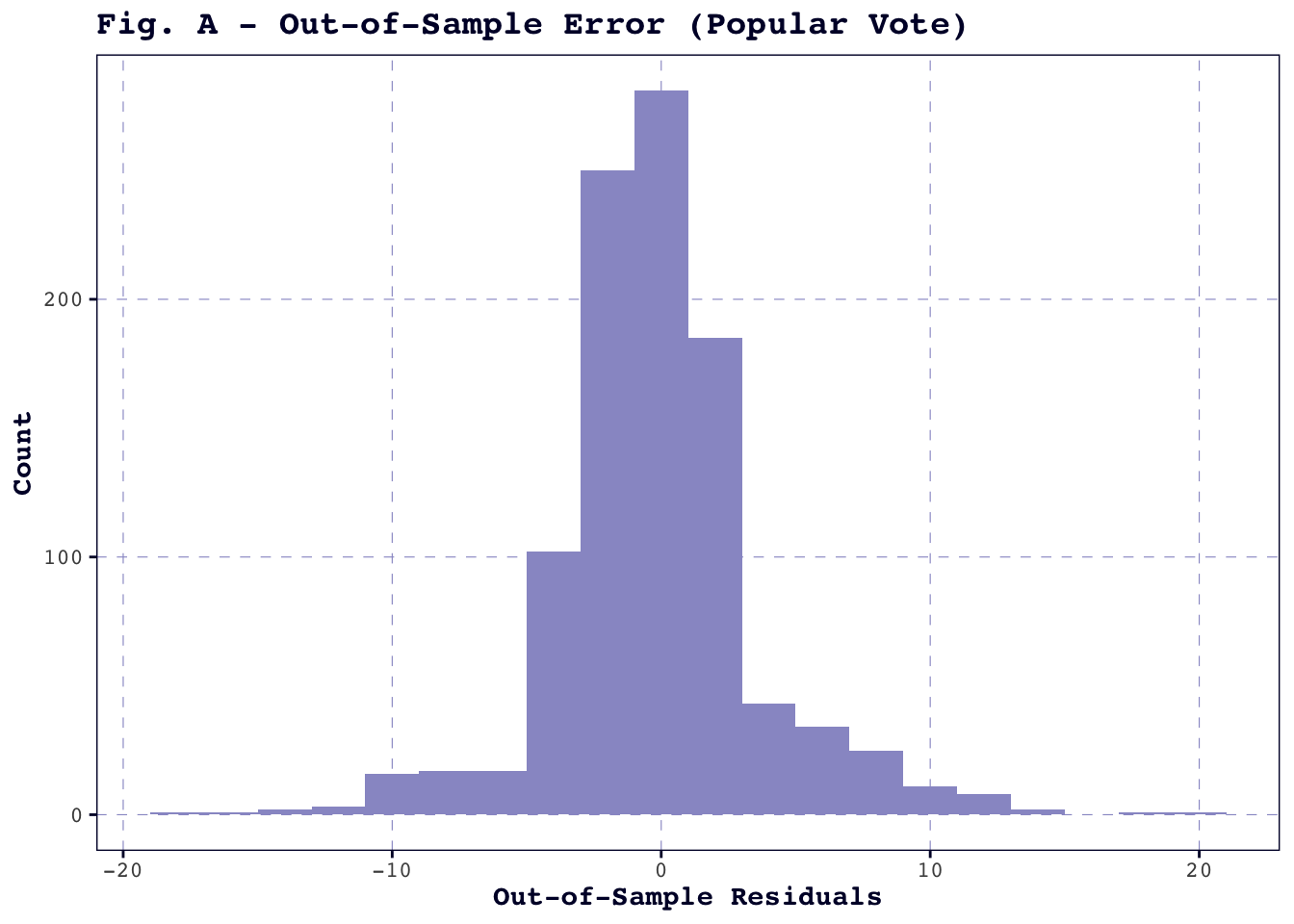

To produce a more robust picture of the uncertainty in the popular vote regression, I also calculated a measure of out-of-sample fit. Whereas R-squared judges the model’s performance against one set of historical data, cross-validation allows for the model to train and test on many different combinations of observations (in this case, election years), which is an enormous benefit in a dataset as small as this one. I ran this particular cross-validation one thousand times, and plotted the residuals – that is, the difference between the predicted Democratic vote share and what was actually observed in the historical data – in Figure A, below.

The result is a respectable normal distribution centered around 0. The mean of the absolute value of the above residuals is 2.65, which is also decent, though of course 2+ points can make or break a popular vote result.

It would certainly be irresponsible, especially in a race this nail-bitingly close, to take any prediction from this model as gospel; if anything, the statistical tests described above just validate the now commonplace notion that this election will be very close.

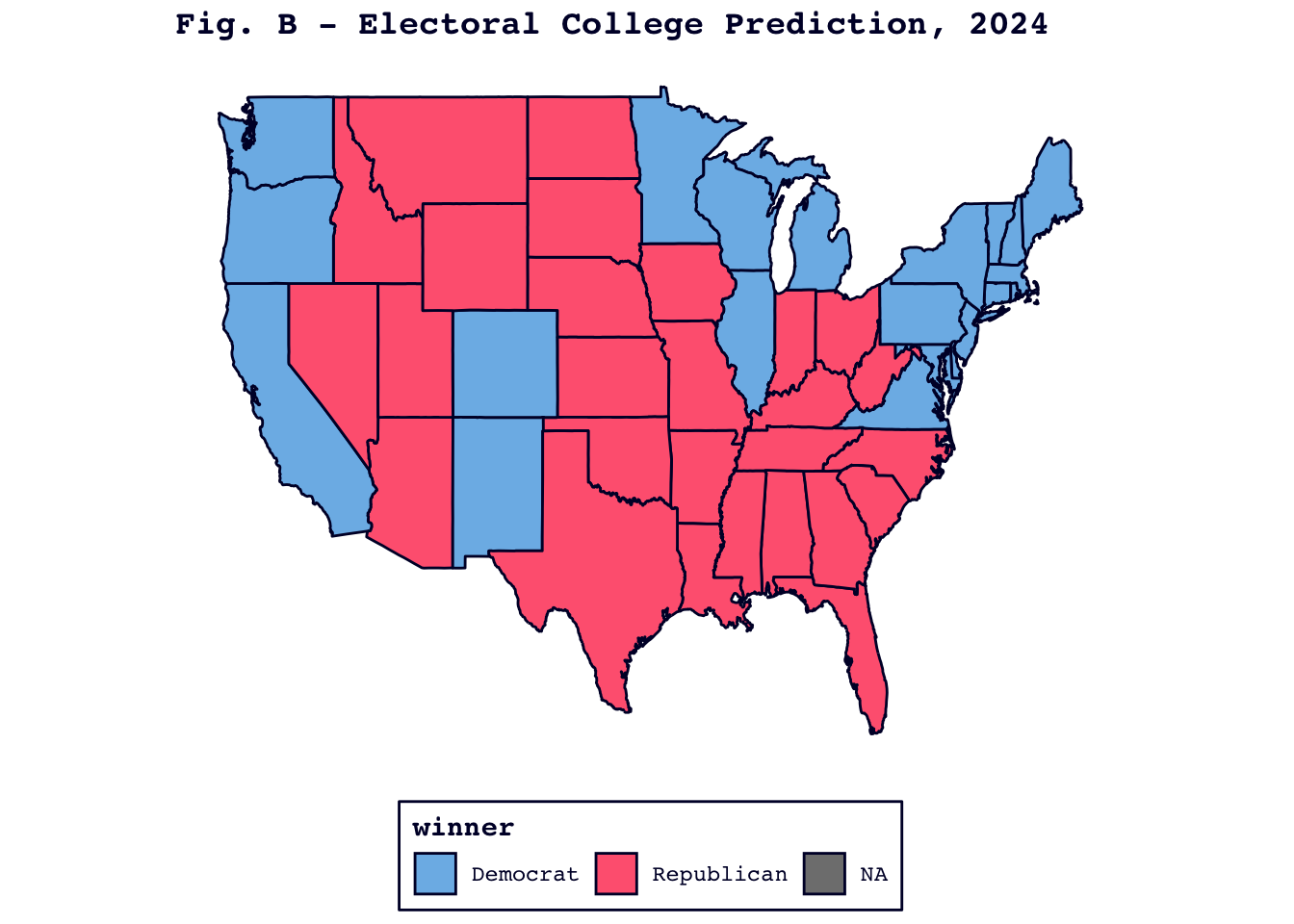

Figure B, below, visualizes this week’s Electoral College prediction, in which Harris squeaks by with 270 electoral votes exactly once D.C.’s three electoral votes are added in.

Last week’s model reached the same conclusion, but imputed state-level polling by adding states’ 2020 poll errors to their 2020 Democratic vote share, instead of the national 2024 polling average. The current model fixes this issue. This seems like a relatively substantial difference, but I think the reason the map did not change is because most of the states that lack current polling – and thus had to incorporate the flawed imputation procedure – are highly unlikely to change their vote from 2020. Although it is harder to perform a sanity check on the swing state predictions, it is at least reassuring that they all have recent polling available.

See you next week!

References

Arnsdorf, I. & Dawsey, J. (2024, August 3). Trump team gambles on new ground game capitalizing on loosened rules. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2024/08/03/trump-allies-ground-game/