Introduction

Welcome to my final prediction for the 2024 presidential election!

With early voting well underway and only a few days left until Election Day, the race remains stubbornly in the toss-up category, according to expert forecasters such as the Cook Political Report and Sabato’s Crystal Ball. My prediction, unfortunately, is no exception to this trend. While I will predict a winner in today’s post, the predictive intervals produced by both my popular vote and electoral college models encompass scenarios in which either candidate could win.

My 2024 Model

My model uses a simple OLS regression, with the following explanatory variables: a dummy indicator of whether the candidate served in a previous presidential administration, Q2 consumer sentiment, lagged vote share, and a recent polling average. The outcome variable is the two-party vote share for the Democratic candidate.

My model is inspired by Abramowitz’s Time For Change model, though I changed the specific indicators (incumbency to previous administration, GDP to ICS, and June approval ratings to recent polls) and added lagged vote share.

Here is the formula for the popular vote regression:

Y = (beta 0) + (beta 1) x A + (beta 2) x C + (beta 3) x L + (beta 4) x P + epsilon

…And here is the formula for the electoral college regression:

Y = (beta 0) + (beta 1) x A + (beta 2) x C + (beta 3) x V + (beta 4) x P + (beta 5) x S + epsilon

I will address each of the variables and their coefficients in the following sections, but first I should briefly discuss adjusted R-squared, a measure of the model’s overall performance. Adjusted R-squared describes the percent of the variation in Democratic two-party vote share that can be explained by the independent variables. For the popular vote, this is about 71%, while the electoral college model, probably since it is more finely tuned to state-level conditions, explains about 78%. While there are ways to inflate R-squared and adjusted R-squared, I think this 71%-78% range, even though it does not account for all possible factors, is respectable for the purposes of this prediction. After all, a sky-high R-squared might seem desirable, but it could indicate overfitting, or hyper-sensitivity to trends in the historical data, which could impair the predictive power of the model.

| Popular Vote Model | Electoral College Model | |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 15.806 | 8.105 |

| Index of Consumer Sentiment (C) | 0.008 | -0.035 |

| National Poll Average, 1 Week Left (P) | 0.674 | -0.033 |

| Candidate Was In Previous Administration (A) | -1.358 | -4.307 |

| Previous Year National Two-Party Vote Share (L) | 0.074 | not included |

| Previous Year State Two-Party Vote Share (V) | not included | 0.6 |

| State Poll Average or Imputed Support, All-Time (S) | not included | 0.425 |

| Number of Observations | 13 | 559 |

| R-squared | 0.806 | 0.779 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.709 | 0.777 |

Previous Administration

I have already written at length about the problem of incumbency in this year’s race, but this, at least, bears repeating: the boons and burdens of incumbency are split between Trump and Harris. He has impeccable name recognition, has been the leader of his party for eight years, and hopes to capitalize off of nostalgia for his first term in office. She inherited Biden’s extensive campaign machinery and must defend the current administration’s record, including on unflattering issues like inflation, immigration, and war in the Middle East. Since my model only predicts Democratic vote share, Trump’s incumbency status is left an open question. Harris, however, must be directly addressed.

I have chosen to use a “previous administration” dummy because I think it comes closest to describing Harris as a non-incumbent who is nevertheless closely linked to the sitting president. A binary indicator for incumbent party membership could also be used here, but it risks underplaying the extent to which voters will evaluate Harris as Biden’s second-in-command. Statistical tests are of little use in this instance, since Biden’s last-minute removal from the race is anomalous. Whether you lend any credibility to this model, then, depends on how you take this judgment call.

Both coefficients – for the popular vote and electoral college models – are negative when the previous administration variable is 1. According to the models, then, being a member of a previous presidential administration is associated with decreased vote share. However, this relationship is only significant in the electoral college model, where members of previous administrations are expected to receive about 4.3 fewer points compared to other candidates.

Index of Consumer Sentiment

My economic indicator of choice is another slight twist on the Time For Change formula. Instead of GDP, I opted for a measure of consumer sentiment, or respondents’ professed impressions of the state of the economy, with the hope of more directly assessing the judgments underlying economic retrospective voting. The choice of this indicator assumes a model of voter behavior in which voters do weigh their personal impressions of the economy but are not substantially subconsciously influenced by fluctuations in GDP that may be influencing economic conditions behind the scenes.

In a previous post, I justified using ICS because I found that using that variable over GDP growth moderately improved both in- and out-of-sample fit. As the table below indicates, this is no longer true. After re-running the comparison on my updated model, I found that GDP growth slightly outperforms ICS in out-of-sample fit, but slightly underperforms in adjusted R-squared, where all other variables are kept constant. Nevertheless, both versions of the model predict similar two-party vote shares for Harris in the popular vote.

| GDP | ICS | |

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | 0.2676 | -0.033 |

| Significant at 0.05 Level? | NO | NO |

| Outliers? | YES | NO |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.763 | 0.709 |

| Mean of Absolute Value of Out-of-Sample Residuals | 2.451 | 2.615 |

| Predicted Dem Two-Party Vote Share | 52.15 | 51.26 |

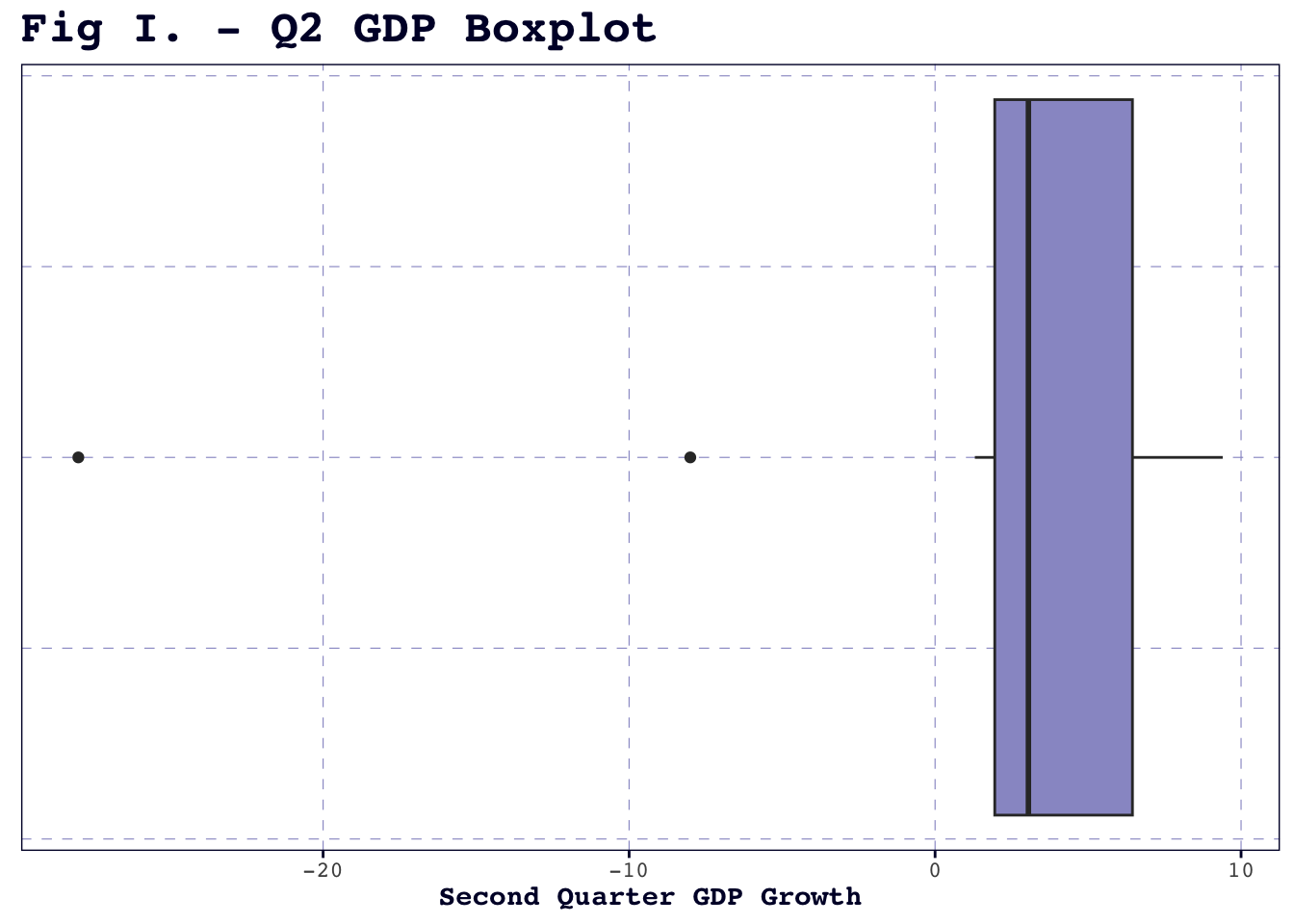

Figure I, below, makes one argument for ICS: unlike GDP, it does not include any outliers in the dataset I used. On the one hand, this makes it easier to justify including otherwise anomalous years, like 2020. On the other hand, the fact that GDP growth drops to a whopping -28 in Q2 of 2020 suggests that there might be very good reasons for dropping unrepresentative years. Both measures are in some respect imperfect, but I decided to move forward with ICS.

The same story we observed for the previous administration variable repeats itself with consumer sentiment. In the popular vote model, the coefficient is substantively low and insignificant. In the electoral college model, it is significant at the 0.05 level and has a small negative estimate of -0.0035. Counterintuitively, this coefficient implies that Democratic vote share drops as Americans’ outlook on the economy improves. If this trend does hold true in reality, it could result from an increased desire for welfare and stimulus programs (associated with the Democratic party) during times of economic hardship and a desire for more limited government intervention (associated with the Republican party) when the economy seems strong.

Lagged Vote Share

Continuity over time is the very basic principle behind the inclusion of a lagged vote share variable. Vavreck’s signature argument that the United States is experiencing a process of calcification (from our GOV 1347 class discussion), whereby partisans are becoming entrenched in their views and more homogeneous among themselves, would suggest that previous cycle vote share will only become a better predictor of voter behavior as the electorate calcifies.

As seems to be the trend for most of these variables, the national lagged vote share variable is insignificant and substantively small, while the state-level lagged vote share is highly significant and has an estimate of 0.6, meaning every additional point for the Democratic party in the preceding election is expected to correspond to 0.6 additional points in the next race. This would be moderately good news for the Harris campaign, since it suggests that she would inherit a slight head start in those battlegrounds which Biden won in 2020.

Poll Average

With polling, we come to the first major distinction between national- and state-level models. The most recent national polling average from FiveThirtyEight’s aggregation – currently set at one week before Election Day, though the polls themselves may have been administered earlier – is featured in both models. I decided to limit national polls to the most recent weekly average in recognition of Gelman and King’s claim that polls become more reliable closer to Election Day, as voters converge on their underlying preferences. However, I also chose to take an all-time average of state-level polls for my electoral college. While ideally I would like to have plentiful recent polls from all states, state-level polls are fewer in number than national polls, and I therefore opted not to restrict my sample further by removing old polls. Hopefully, this two-pronged approach gives my electoral college model the best of both worlds: the recent national average should act as a temperature check for Harris’s overall trajectory across the country and the long-term state average should offer an insight into state-level preferences that is more resistant to short-term fluctuations.

Unfortunately, in some cases, state-level polling is not yet available. For these states, I imputed a poll average by applying their deviation from the national popular vote in 2020 to the current national average. In this past week, polling data became available for four states that I had previously imputed, so I took the opportunity to compare the results of my imputation to the actual polls.

| State | Dem Two-Party Vote Share (Polls Available) | Dem Two-Party Vote Share (Polls Imputed) |

|---|---|---|

| Indiana | 41.47 | 41.76 |

| Massachusetts | 65.48 | 66.95 |

| Nebraska | 40.19 | 40.18 |

| Washington | 59.28 | 59.79 |

As the above table indicates, my imputation procedure generated very similar predictions to what my model is now predicting given new polling data. While none of these states are highly contested – and, for that matter, none of remaining imputed states are battlegrounds – it is reassuring that the biggest shift was just 1.47 points in Massachusetts.

In the popular vote model, the national poll average (P) just barely misses the threshold for significance at the 0.05 level. Its coefficient, 0.674, suggests that a one-point increase in Democratic support in the national poll average corresponds with a 0.674 increase in Democratic vote share. In the electoral college model, the national average has a small negative coefficient that is not significant. Interestingly, the coefficient is negative, which, if true, would imply that Democratic vote share in the states slightly declines as support in the national polls rises. However, the state-level average is highly significant and has a coefficient of 0.425, which could be a substantial pay-off in state-level vote share.

Out-of-Sample Tests

To further assess the model, I conducted a cross-validation procedure on the popular vote model and re-ran the electoral college model to “predict” the 2016 and 2020 election cycles.

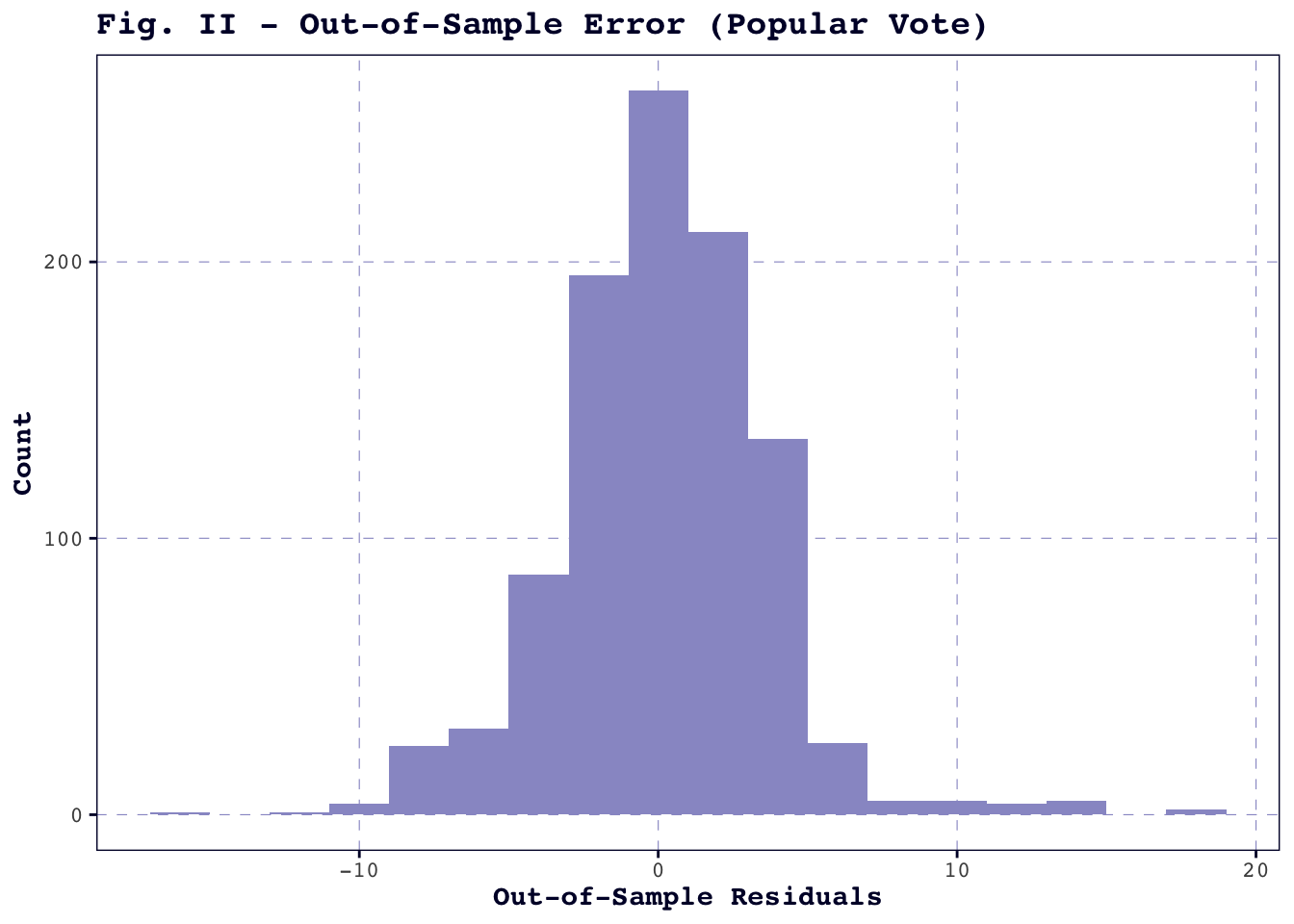

Figure II, below, summarizes the out-of-sample residuals from the cross-validation exercise. The distribution is roughly normal, as expected, and the mean of the absolute value of the out-of-sample residuals is about 2.615. In the context of a bitterly close election, of course, 2.615 points is nothing to sniff at. However, given the range in observed vote share found in the historical data is around 16.6 points, and that this degree of out-of-sample error is in line with the predictive models I have produced in previous weeks, I have continued with this model.

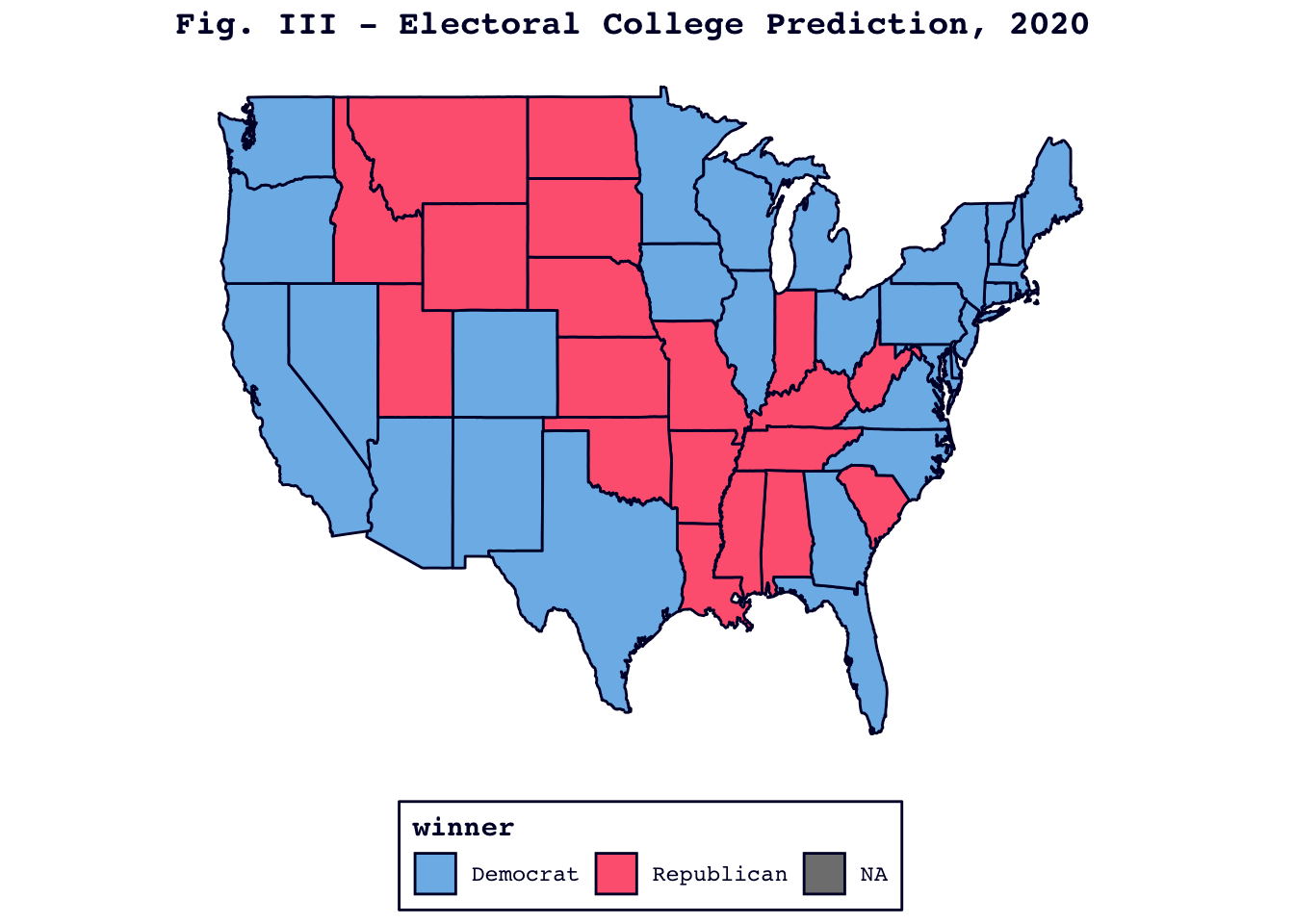

Next, I created an electoral college “predictions” for 2020. Figure III, below, illustrates which states my model would expect Biden to win and lose in 2020.

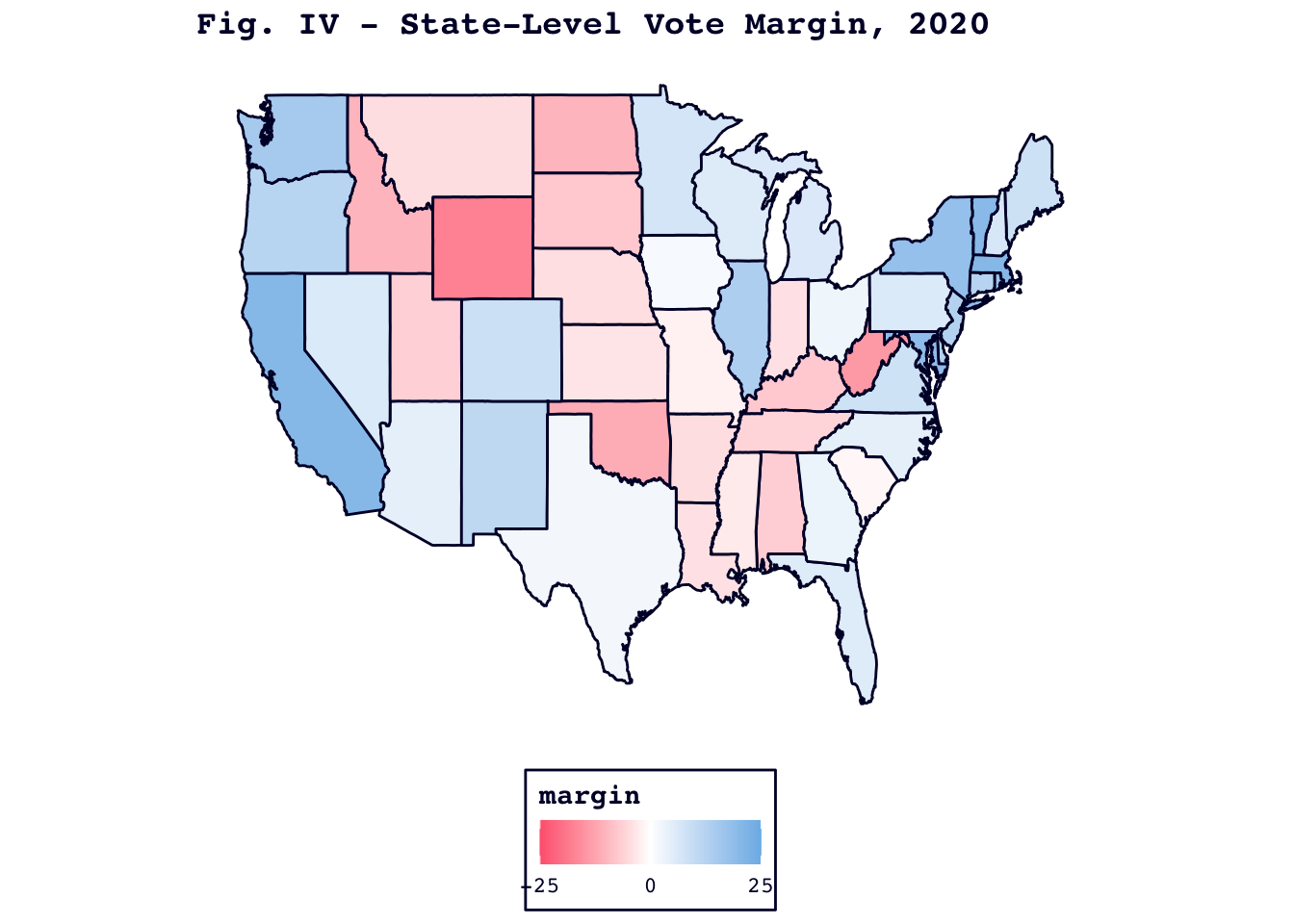

There are, as I am sure you have noticed, several things wrong with this map. Not only does it predict a blowout victory for Biden with 409 electoral votes, but it does so by handing him improbable wins in states like Texas and Florida. On the other hand, Figure IV, which displays Biden’s predicted margins in each state, makes these ludicrous upfront results seem a bit more sensible.

The margins map, above, at least gives margin a very narrow margin of victory in Texas and Florida. Rather than throwing all of the states randomly out of whack, the model seems to have preserved the basic relative values of the states, but shifted the whole prediction slightly leftward. This is particularly interesting since, as we will soon see, my 2024 prediction from the same model appears to have the opposite skew.

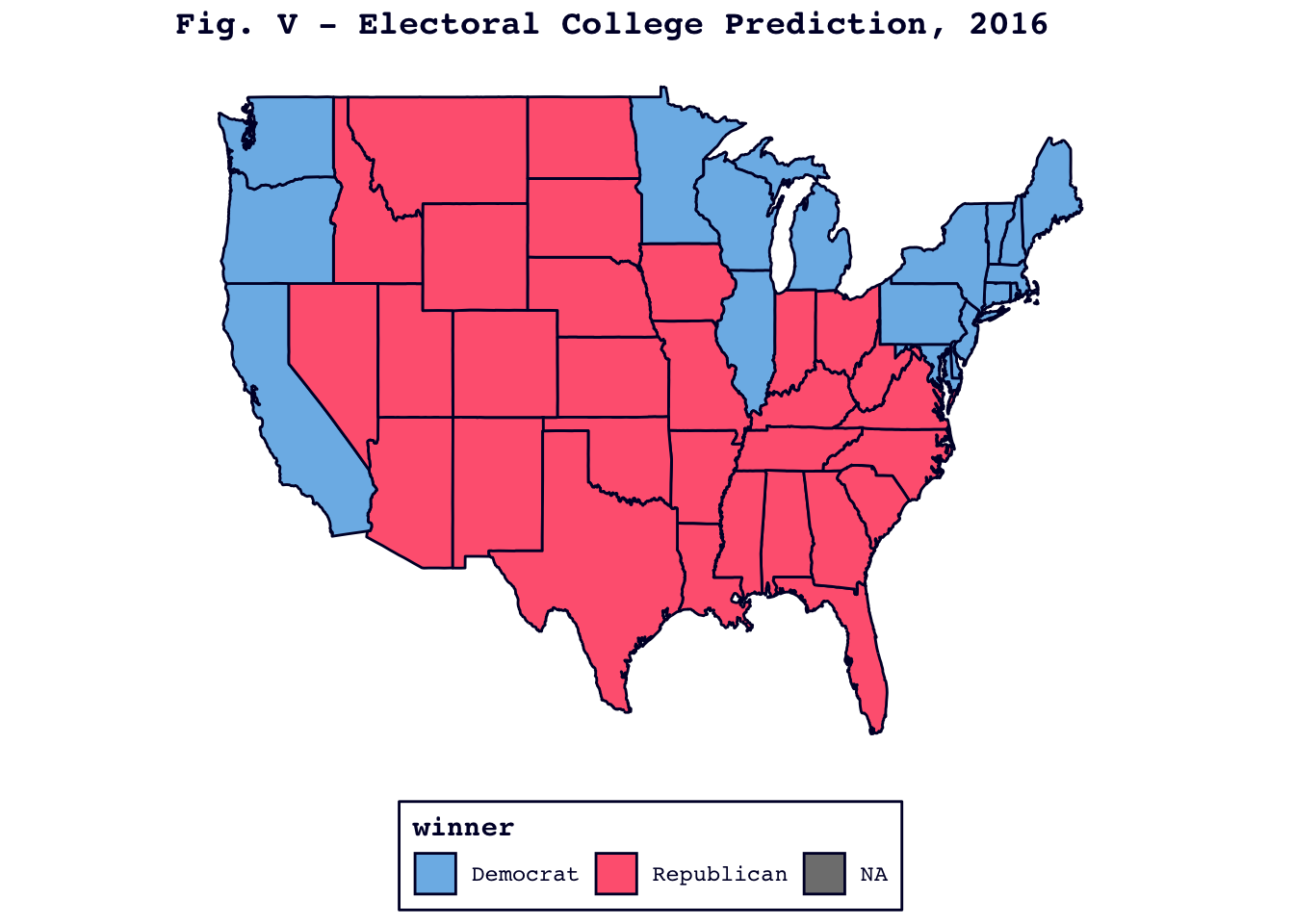

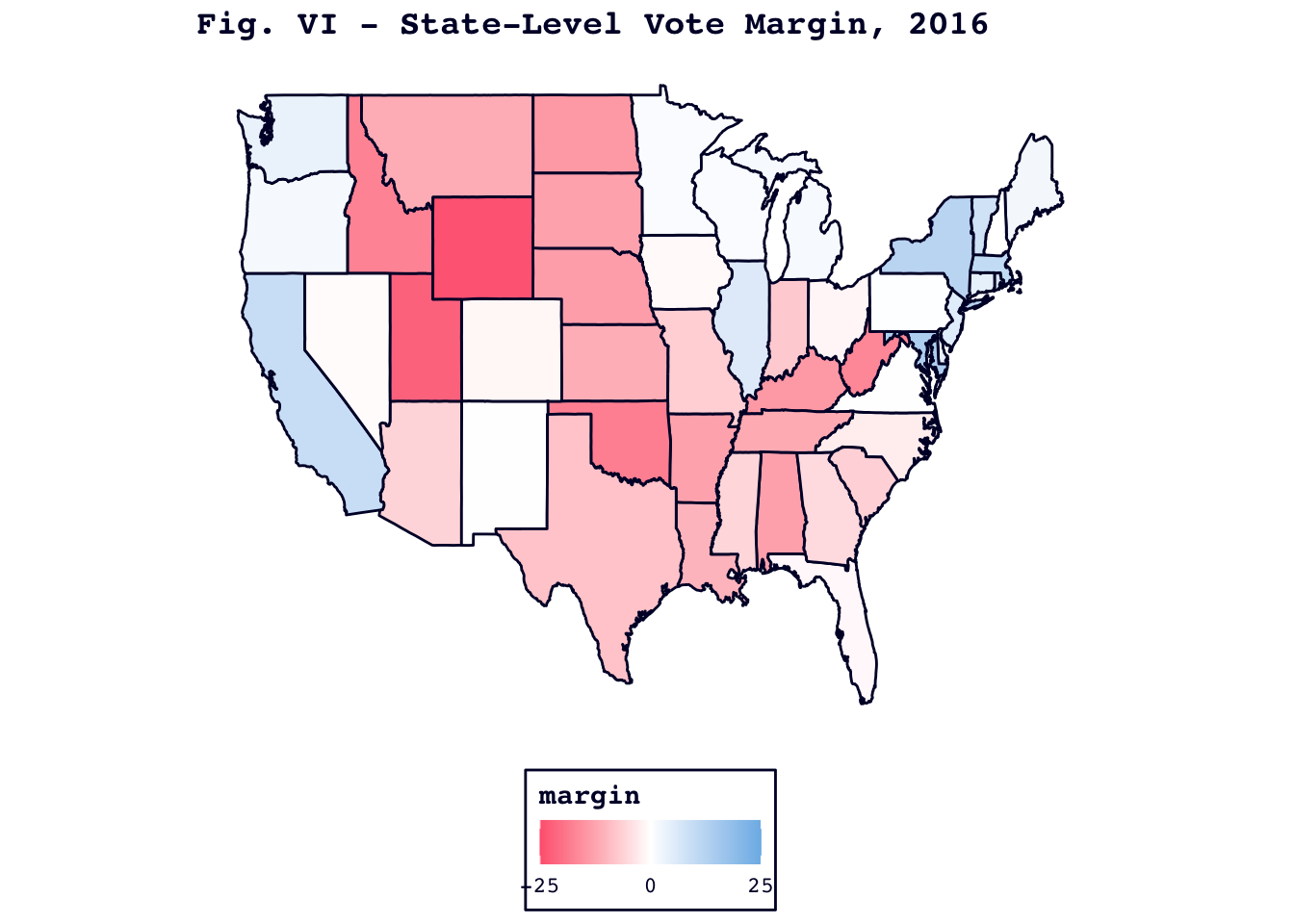

As a final check, I used my model to “predict” the 2016 election, with similarly bizarre results. While Figure V, below, shows that my model did predict a Trump victory, it shortchanged Clinton in Colorado, New Mexico, and Virginia, despite handing her wins in the Blue Wall states.

Once again, Figure VI indicates that these mistakes come from states with very narrow predictive margins.

Ultimately, my model is only as good as the data that it receives. These alternate-reality maps of 2016 and 2020 are a reminder that my model rests on the – possibly fragile – hope that the same pollsters who veered in the wrong direction, say by underestimating Trump in 2016, will not make a similar systematic error in 2024.

Popular Vote Results

Without further ado, it is time to unveil my predictions for the 2024 presidential election!

First, my popular vote prediction is summarized in the table below. I am predicting a 51.26% Harris two-party vote share. At the 80% confidence level, my predictive interval crosses the 50% mark, so my model cannot identify a clear winner.

| Dem Two-Party Vote Share | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

|---|---|---|

| 51.26 | 46.52 | 55.99 |

I should also note that Harris’s predicted margin of victory under this model has declined in past weeks, as recent national polls favoring Trump have poured in.

Electoral College Results

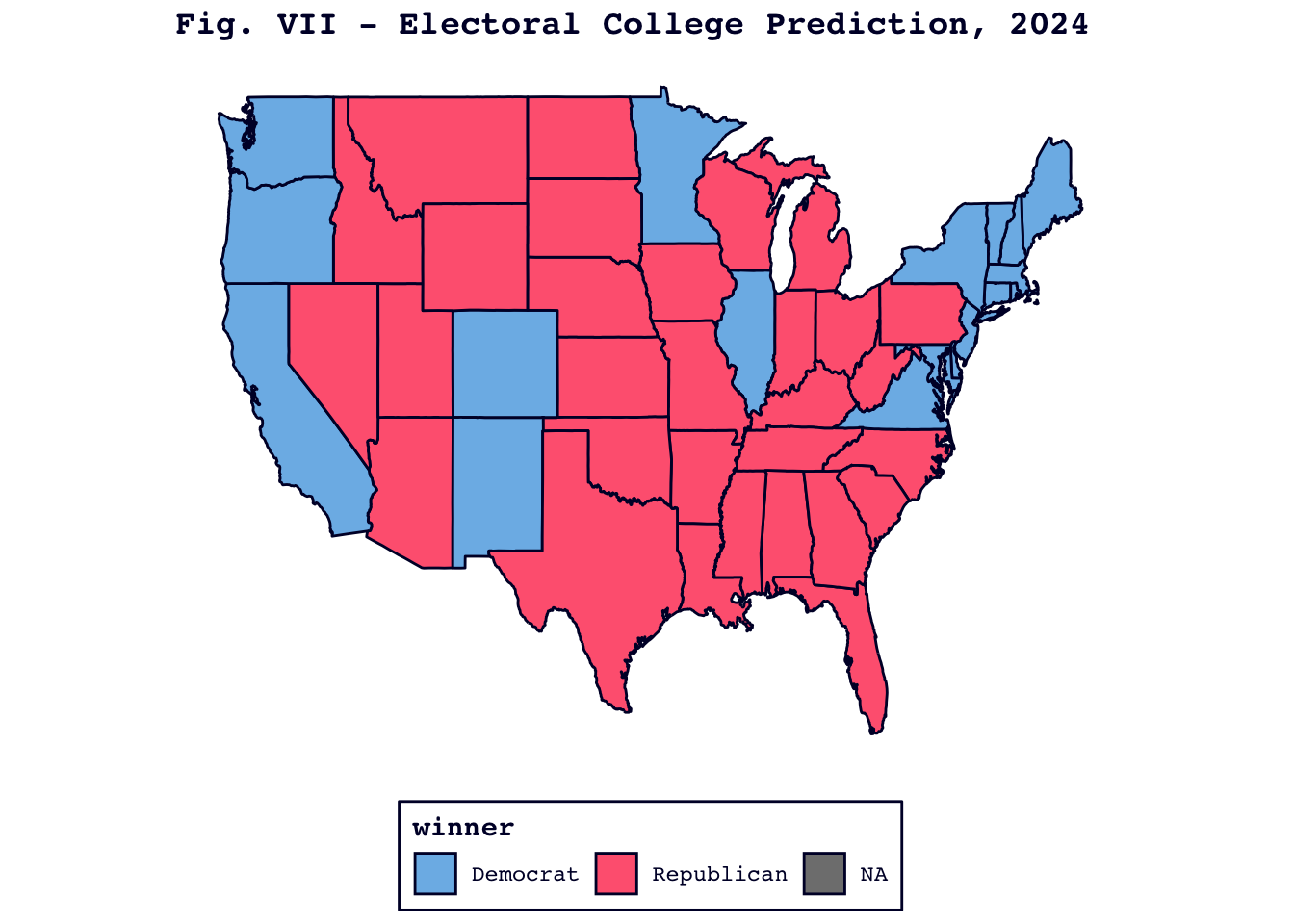

Finally, and most importantly, here is my electoral college prediction: my model predicts that Harris will receive 226 electoral college votes and Trump will take the presidency. The map in Figure VII is supplemented by the table below, which gives predictions for the unpictured states of Alaska and Hawaii, as well as the District of Columbia. In the absence of robust historical polling data, I did not create separate predictions for the congressional districts of Nebraska and Maine. Since my model predicts a comfortable victory for Trump in the electoral college, these additional data points, though interesting, would not change the big picture of my prediction.

| Region | Dem Two-Party Vote Share | Winner |

|---|---|---|

| Alaska | 42.53 | Republican |

| District Of Columbia | 94.12 | Democrat |

| Hawaii | 71.77 | Democrat |

The table below zooms in on the seven swing states of this election cycle. While all of the predictions are centered below 50, with Trump predicted to win, every single interval crosses the decisive 50% mark at the 80% confidence level.

| State | Dem Two-Party Vote Share | Lower | Upper | Winner |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 47.58 | 41.98 | 53.18 | Republican |

| Georgia | 47.64 | 42.04 | 53.23 | Republican |

| Michigan | 48.92 | 43.33 | 54.52 | Republican |

| Nevada | 47.88 | 42.28 | 53.48 | Republican |

| North Carolina | 46.99 | 41.39 | 52.58 | Republican |

| Pennsylvania | 48.58 | 42.98 | 54.18 | Republican |

| Wisconsin | 48.40 | 42.80 | 54.00 | Republican |

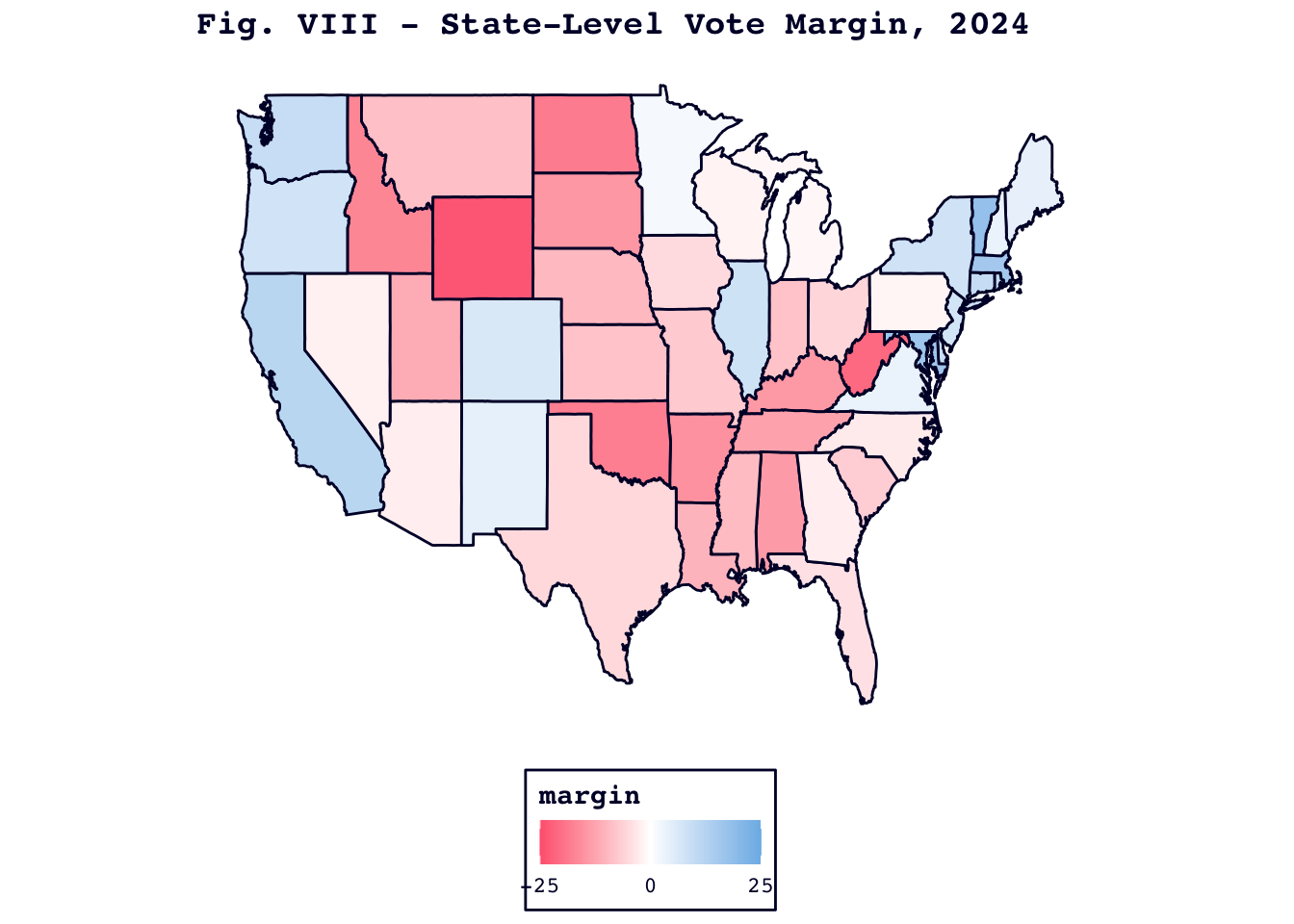

Thank you for joining me for this tour of my 2024 predictive model. I will leave you with Figure VIII, a map of the predicted margins for each of the continental states. From where I sit now, on Monday, November 4th, 2024, it seems like a reasonable guess. Only time will tell if four years from now this map will look as bizarre as my 2020 and 2016 “predictions.”

References

Cook Political Report. (2024, November 1). 2024 CPR President race ratings. https://www.cookpolitical.com/ratings/presidential-race-ratings

Gelman, A. & King, G. (1993, October). British Journal of Political Science, Vol. 23 (4), 409-451. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400006682

Mercer, A., Deane, C. & McGeeney, K. (2016, November 9). Why 2016 election polls missed their mark. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2016/11/09/why-2016-election-polls-missed-their-mark/

Sabato’s Crystal Ball. (2024, September 25). 2024 Electoral College ratings. The Center for Politics at the University of Virginia. https://centerforpolitics.org/crystalball/2024-president/