Welcome back! Now that the dust has (more or less) settled, I am back on the blog to reflect on my model’s performance on Election Day.

A Tale of Two Models

As a reminder, the following table summarizes the basic characteristics of my two models.

| Popular Vote Model | Electoral College Model | |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 15.806 | 8.105 |

| Index of Consumer Sentiment (C) | 0.008 | -0.035 |

| National Poll Average, 1 Week Left (P) | 0.674 | -0.033 |

| Candidate Was In Previous Administration (A) | -1.358 | -4.307 |

| Previous Year National Two-Party Vote Share (L) | 0.074 | not included |

| Previous Year State Two-Party Vote Share (V) | not included | 0.6 |

| State Poll Average or Imputed Support, All-Time (S) | not included | 0.425 |

| Prediction for Harris 2024 | 51.26% Two-Party Vote Share | 226 Votes |

The first three explanatory variables – C, P, and A, in the table above – are exactly the same across both models. Together, they roughly mirror the three facets of Abramowitz’s Time for Change model: a measure of economic performance, a survey of public opinion, and an indicator of incumbency status.

The models are differentiated by the final two components: lagged vote share and state-level polling. My goal was to make the models as similar as possible, so both incorporate a measure of previous year Democratic two-party vote share, but the popular vote model only uses the national result (L), while the electoral college model uses state results (V). S, an all-time state-level polling average, is the only variable with no equivalent in the popular vote regression. Since polls are not – or were not, at the time that I finalized the prediction – available in all states, S also has some internal inconsistencies, as “missing” states were populated by applying their deviation from the national popular vote in 2020 to P, the most recent national polling average from 538.

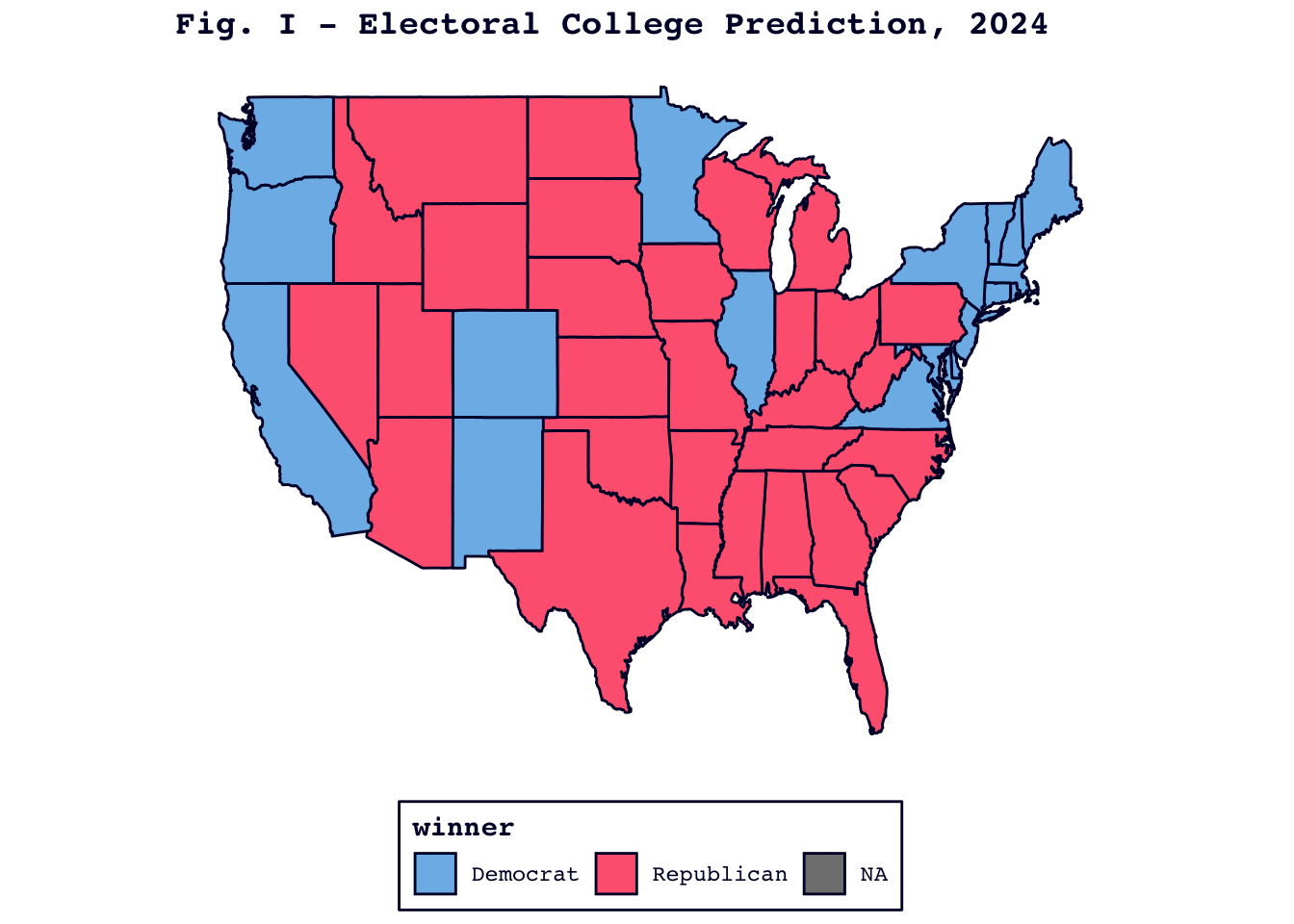

Intriguingly, my electoral college model hit the mark (see Figure I below, which correctly predicts Trump’s sweep of the battleground states) while my nearly identical popular vote model floundered, predicting a Harris victory that clearly has not come to pass.

Assessing My Popular Vote Model

Let’s start with what went wrong: the popular vote model.

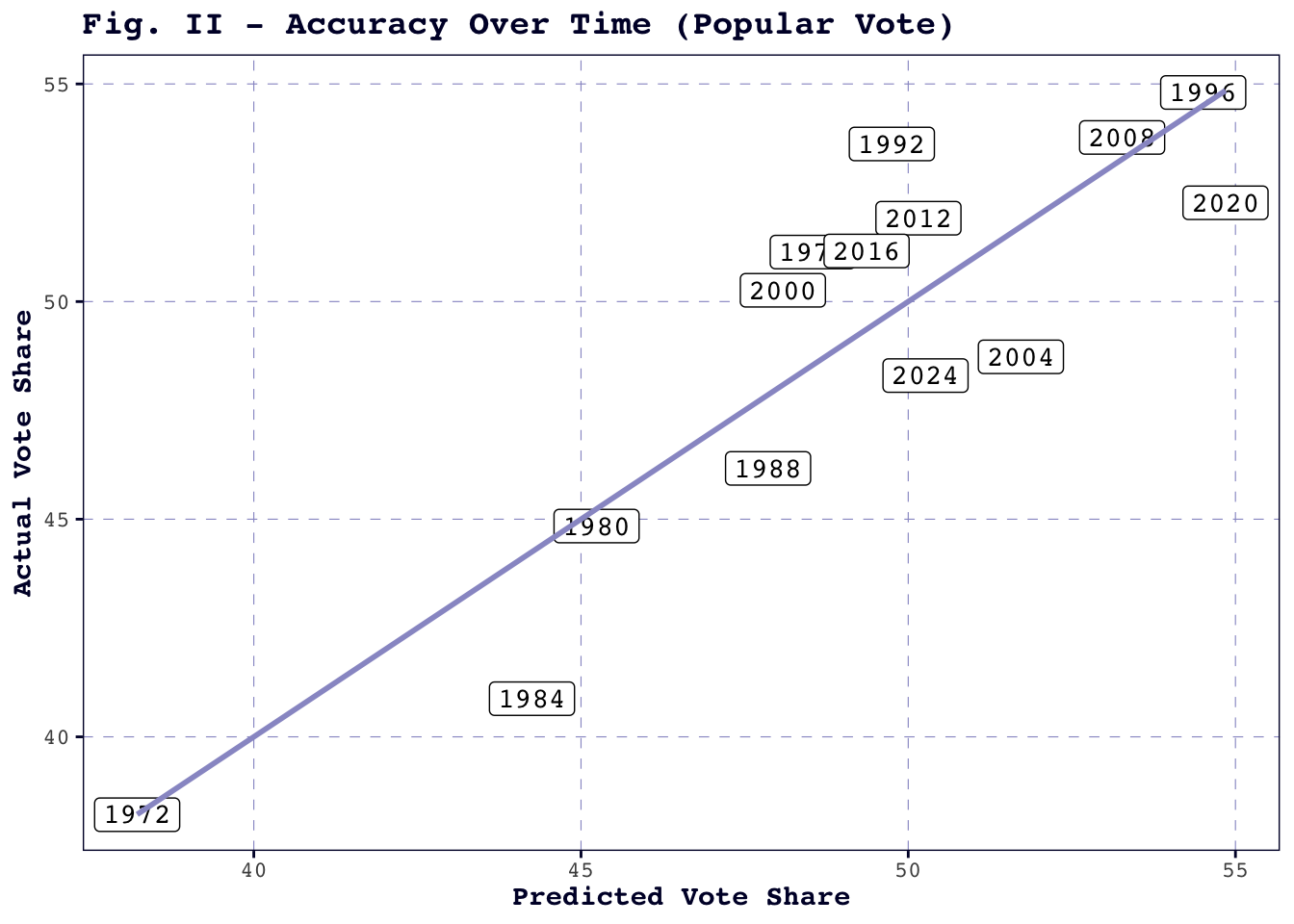

When we zoom out to look at the model’s predictions over multiple election years, the model’s accuracy begins to look more respectable. Figure II shows that the historical elections are well distributed along the fitted line, with 2024 falling roughly in the middle of the pack in terms of accuracy.

Admittedly, the data points are few and far between, but based on this visualization, the model does not seem to be getting substantially better – or worse – over time. The model does slightly overestimate Democratic vote share in 2020 and 2024, but I am hesitant to take those two observations as proof of a systematic tendency to underestimate Trump, especially since the model is inclined to underestimate Clinton’s vote share in 2016.

Next, I tweaked the regression formula, one element at a time, with the hope of weeding out any problematic variables. The results of this investigation can be found in the table below.

| Adjusted R-squared | 2024 Bias (Actual - Predicted) | Mean Squared Error | Root Mean Squared Error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Variables | 0.69 | -1.96 | 4.78 | 2.19 |

| No Polling Average | 0.60 | -0.04 | 7.03 | 2.65 |

| No Index of Consumer Sentiment | 0.72 | -2.05 | 4.83 | 2.20 |

| No Previous Administration Dummy | 0.69 | -3.34 | 5.47 | 2.34 |

| No Lagged Vote Share | 0.69 | -2.76 | 5.30 | 2.30 |

| Swap GDP Growth for ICS | 0.73 | -2.51 | 4.25 | 2.06 |

| Swap Incumbent Party for Previous Administration | 0.65 | -3.40 | 5.47 | 2.34 |

Generally speaking, the adjusted r-squared improvements were minimal. In most cases, dropping or swapping a variable produced a model that explained only about as much, if not less, of the variation in Democratic two-party vote share.

The exceptions to this are the model that dropped ICS and the model that substituted GDP growth in its place. In both cases, I should note, the percentage of variation explained increased by a modest 3 to 4 points, the MSE (mean squared error) and RMSE (root mean squared error) barely moved, and the resulting prediction overestimated Harris more severely than the original model. While I am not convinced that consumer sentiment is the driving factor behind my model’s failure in 2024 specifically, there seems to be reason to be cautious of consumer sentiment’s long-term predictive power, at least when it is serving as the sole economic indicator.

The other standout from this table is the “no polling average” model, which yielded a 2024 national popular vote prediction that was just 0.04 points over Harris’s two-party vote share (though the actual number may shift slightly in the coming days and weeks as the last votes are tallied). This improvement, however, comes at the cost of a lower adjusted r-squared and the highest MSE and RMSE of all seven models – this is perfectly fine if the model’s only purpose is to predict the 2024 results, but it could compromise its ability to generate plausible predictions for future elections.

So far, we have identified two possible weakness areas: polls and consumer sentiment. I will revisit both and offer substantive hypotheses in the final section of this post. For now, we should check in on the electoral college model.

Assessing My Electoral College Model

Predicting a winner in each state is one thing – the real challenge is predicting state-level vote share, and my model had its fair share of mistakes in that respect.

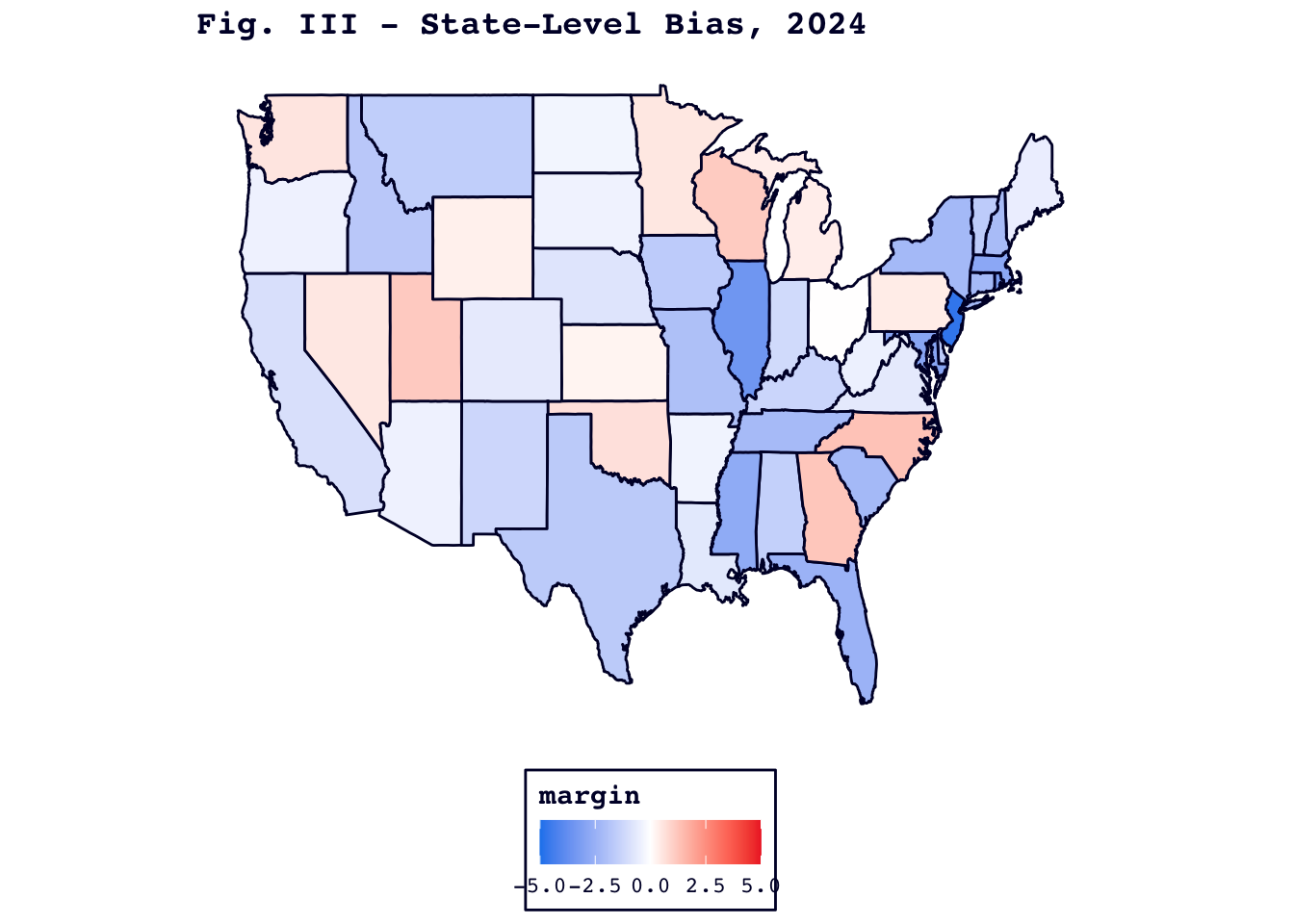

Figure III, below, displays each state’s prediction error. Blue states had predictions that overestimated Harris’s eventual vote share, while red states underestimated her.

The most biased states were New Jersey (-4.7 points) and Illinois (-3.5 points). By contrast, the state most biased in favor of Trump, North Carolina, was much closer to that state’s observed vote share (+1.3 points).

The following table breaks these results down by two salient characteristics: poll availability and battleground status.

| All States | Polls Imputed | Polls Available | Battlegrounds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias | -1.06 | -1.33 | -0.73 | 0.65 |

| Mean Squared Error | 2.94 | 3.30 | 2.24 | 0.75 |

| Root Mean Squared Error | 1.71 | 1.82 | 1.50 | 0.86 |

| Mean Absolute Error | 1.39 | 1.49 | 1.26 | 0.77 |

The first takeaway from this table is that, on average, my model overestimated Harris’s performance. This in itself is interesting, since I ultimately predicted a comfortable Trump win in the electoral college, and the second and third columns help shed some light on this discrepancy.

As I mentioned earlier, I had to rely on an imputation procedure for the 27 states (and one district) that did not have accessible polling data for 2024. These states (New Jersey and Illinois included) seemed to have received predictions that were more biased in favor of Harris than the nation as a whole.

Where polls were available, they seem to have yielded better, though still slightly left-skewing, predictions. This is yet another mystery to tuck in your back pocket for later: national polls seem to have, if anything, overinflated Harris’s vote share in my popular model, but state-level polls nudged my electoral college predictions to the right.

Still, the table has one more surprise in store: the battleground states. All seven swing states had polling data available, but their predictions were even less favorable to Harris than in non-competitive polled states. In fact, my battleground predictions slightly underestimated Harris’s actual performance. Here, perhaps, is evidence of the Harris campaign apparatus at work.

Failures, Successes, & Hypotheses

In the following several sections, I will discuss some possible blindspots in my models. Though I will not resolve these issues in full today, I will outline a few strategies that could be implemented given enough time and sufficiently robust data.

Global Context

A Financial Times article made waves in the days after the 2024 election by asserting that Democrats were fighting an uphill battle against global anti-incumbent sentiment this year. The main evidence for this claim is the observation that incumbent parties across all developed countries experienced declining vote share in 2024. The statistic is compelling, but it is not particularly useful as a predictor unless it is true that global incumbents tend to experience parallel dips and surges in response to international crises and recessions.

If this relationship does hold true, and Harris was doomed from the start, it would probably be advisable to incorporate some indicator of global incumbents’ performance as a “temperature check” on hostility to the ruling party in the developed world. To assess the legitimacy of this claim, however, I would first run a series of regressions with foreign vote share as a predictor. I would be interested to see not just the predictive power of averaged incumbent party vote share in the developed world, but also how each individual country performed; if, say, Canadian vote share tracks American outcomes more closely than other developed nations, I would want to be able to make a regional distinction in my model. Additionally, I would like to see to what extent the potential mechanisms of global anti-incumbent trends that the author identifies, such as inflation, unemployment, and immigration, are historically correlated with incumbent vote share in the developed world.

Inclusivity of “Previous Administration”

I opted to use a binary indicator of membership in a previous presidential administration, because I hypothesized that voters would link Harris to the Biden Administration to a greater extent than they would another same-party heir. Ideally, I would have liked to have a dummy variable for sitting vice presidents, but the election dataset is already very limited, and I was hesitant to whittle it down even further by focusing on an even narrower subset. It would only take one anomalous vice-president-turned-presidential-nominee to throw the coefficient out of whack and jeopardize the model.

Nevertheless, the previous administration variable has its own flaws. Namely, it is probably over-inclusive: former presidents, vice presidents, and cabinet secretaries may all technically qualify, but they have varying levels of visibility and specialization, which could drastically impact voters’ perceptions of them as candidates. My model is blind to these distinctions – a serious shortcoming in a race that has often been dominated by discussions of how Harris did, or did not, distinguish herself from Biden.

If I were to pursue this question further, I would turn to text analysis. One approach would be to simply tally references to the incumbent administration’s members, policies, or slogans, but this could fail to catch important differences in tone: a candidate quite hostile to the administration could be misleadingly classified as strongly associated with the incumbent, even if they referenced the administration in a critical way. Instead, maybe I could apply a two-step process, by first extracting references to key individuals and policies from the candidate’s speeches, interviews, or social media posts, then creating a corpus consisting only of those references, and finally conducting a simple positive/negative sentiment analysis on those excerpts. This approach, however, would be computationally expensive, and it could impose further restrictions on my sample, since text samples from historical elections are likely to be harder to come by.

Name Recognition

The name recognition problem is an extension of the aforementioned ambiguity around Harris’s incumbency status. I hypothesize that the previous administration dummy lumps Harris in with candidates with greater name recognition in their respective election years, and thus contributes to overestimating her performance in the noncompetitive states. If Harris was able to narrow the name recognition gap through sustained campaign activity in the battleground states, but made no comparable effort in noncompetitive states, disengaged voters might have been attracted to Trump’s unquestionably well-known name at the polls. This could help explain my model’s overestimation of Harris’s vote share outside of the swing states.

Specific survey questions might address this concern, except I am skeptical that voters who are so disengaged that they may not be familiar with Harris would be responsive to such polls. If I were to attempt to test my hypothesis, I would instead use a matching procedure to pair geographically and demographically similar counties in battleground and non-battleground states, and then interpret the difference in matched county-level vote share as the average treatment effect of campaign activity.

Ambiguity of Consumer Sentiment

I chose to use consumer sentiment as my economic indicator in no small part because of its ambiguity. My thought process was that the Index, with its sweeping questions about past economic performance, future expectations, and perceived purchasing power, would allow respondents to fill in their own subjective tests of economic health – the same considerations, in theory, that they would reach for on Election Day. This, of course, is too rosy a view of the actual Index. Its approach of combining five equally weighted questions about different facets of the economy serves a purpose, to be sure, but it does not take into account whether voters hold presidents more or less accountable for certain conditions.

If I were able to design my own survey with the goal of predicting election outcomes, I would want to separate out the questions, and run models with each to see whether, say, expectations of a coming recession or confidence in making major household purchases is a better predictor. Additionally, the Index asks respondents to reflect on their financial status, or expected status, in the year before and after the survey date. In an ideal world, I would like to test several different intervals – a year, a quarter, a presidential term, etc. – to more precisely identify the time frame retrospective voters are most inclined to consider. In this particular year, it would be interesting to see whether voters feel that they were better off financially during the first Trump administration.

A Polling Paradox

I have left the most pressing question for last: why did polls improve my electoral college predictions and mislead my popular vote model in the very same election cycle?

The answer, I think, lies in the type of polls involved.

My popular vote model exclusively uses 538’s national polling average from the week before Election Day, under the assumption, taken from Gelman and King, that voters will converge on their intended candidate in the final stretch of the campaign. However, it could also be the case that, in the run-up to Election Day, pollsters under pressure to land on the “correct” estimate exhibit more herding behavior, and that post-hoc re-weighting and/or reluctance to release outlier results creates a systematic bias in the last-minute average. If that was the case this year, a slight initial skew in favor of Harris – whether it resulted from pure chance or left-leaning pollsters putting their thumbs on the scale – could have played a role in the failure of my model.

To test this, I would first compare the prediction generated with 538’s weighted average to RealClearPolitics’ simple average, to see if 538’s pollster ratings exacerbated the potential herding problem, and I would also examine historical data, broken down by pollster, to see how variance between pollsters develops immediately before Election Day. I might also want to look at trends in pollsters’ output over time – it seems unlikely that pollsters would disclose that they decided not to publish a faulty poll, but a drop in publicized data before Election Day could perhaps provide a hint at these behind-the-scenes practices.

Despite these reservations, the decent performance of both of my models leads me to think that the last-minute national polling average is not without its benefits. In the case of the electoral college model, combining the weekly national average with an all-time state-level polling average, which should in theory be more resistant to short-term shocks, seems to have done a better job of predicting voter behavior. This, too, makes a certain amount of sense. It can be convenient to describe voters in unambiguous terms – myopic, retrospective, disengaged, etc. – but in practice, there is no way of neatly separating long-term preferences from last-minute jolts. Many voters will wrestle with both at the ballot box, and both have their role to play in the models.

That’s All, Folks!

Thank you for joining me this week! This is, unfortunately, the end of the road for these particular predictive models, but I look forward to returning in a few weeks’ time with my final post, which will discuss the election through the lens of Nebraska politics. See you then!

References

Burn-Murdoch, J. (2024, November 7). Democrats join 2024’s graveyard of incumbents. https://www.ft.com/content/e8ac09ea-c300-4249-af7d-109003afb893

Gelman, A. & King, G. (1993, October). British Journal of Political Science, Vol. 23 (4), 409-451. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400006682