Campaigning in the Cornhusker State

Welcome to the very final installment of my 2024 election blog!

Today, I will be zeroing in on Nebraska and dissecting the campaign activity in the state in the hopes of figuring out why forecasters (including myself!) might have missed the true outcome.

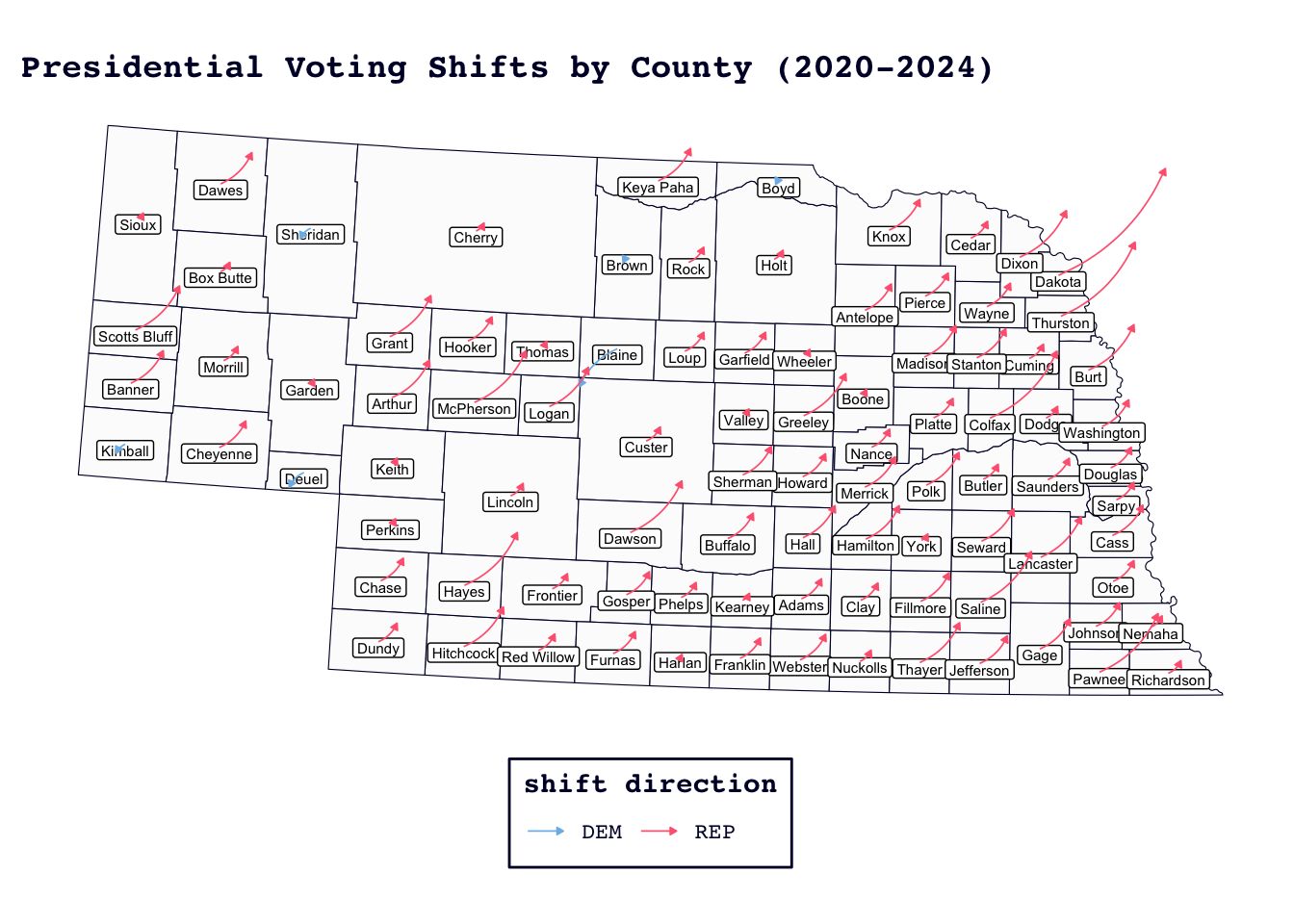

For starters, the map below depicts the county-level swing from 2020. Almost all of Nebraska’s counties experienced an increase in Republican vote share relative to the 2020 cycle.

The few exceptions – Kimball, Boyd, Brown, Sheridan and Deuel – are all ruby red, sparsely populated rural counties in Nebraska’s third district. Their slight leftward swings could just be random noise that their electorates are simply too small to drown out.

On the other hand, the red swing is present but modest in Omaha’s Douglas County and the surrounding areas which make up Nebraska’s second and first congressional districts. This is, of course, despite the fact that Harris did win NE-2’s one electoral vote. While it is impossible to know exactly what the magnitude of the swing might have been if either of the campaigns pursued different strategies in NE-2, it is a question worth keeping in mind – especially since, as we shall see, both Trump and Harris had their eyes on Nebraska’s famous “blue dot.”

Before we get any further, though, I should establish how the predictions stacked up against this reality. Since my model was reliant on historical polling data, and I could not source sufficient observations for Nebraska’s congressional districts, I only generated a statewide prediction. To compensate for this missingness, I have also included predictions from 538 and ratings from the Cook Political Report.

| Unit of Analysis | Harris Two-Party Vote Share (2024) | My Prediction | 538’s Prediction | CPR Rating | Biden Two-Party Vote Share (2020) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statewide | 39.4 | 40.2 | 41.3 | Solid R | 39.2 |

| CD-1 | 43.4 | NA | 41.6 | Solid R | 43.3 |

| CD-2 | 52.3 | NA | 53.5 | Likely D | 52.2 |

| CD-3 | 22.8 | NA | 22.6 | Solid R | 23.1 |

Ultimately, all of the top-line outcomes were predicted correctly: Trump won statewide and in the first and third congressional districts, and Harris won the second congressional district. My statewide prediction was slightly closer to the outcome than 538’s, perhaps due to overfitting in their higher-dimensional model. In any case, both my model and the 538 model slightly overestimated Harris’s statewide vote share.

If we break the 538 predictions down by congressional district, we get what appear to be three quite different stories: the model was almost dead-on in NE-3, overestimated Harris by 1.2 points in NE-2, and underestimated her by 1.8 points in NE-1. Since 538’s model performed remarkably well in NE-3, a district which also received very little attention from either presidential campaign, I will confine my remarks to the other two districts and the statewide result, with special attention to NE-2.

Nebraska: An Overview

Demographics, Geography, & Electoral History

Nebraska is a Republican bastion in the heart of the Great Plains. A Democratic presidential candidate has not won statewide in Nebraska since Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964 and the state has consistently elected Republican governors since 1998.

Nebraska does tick some boxes in the “Republican stereotypes” column: it is highly rural, ranking 43rd in the nation for population density, and has a large proportion of non-Hispanic whites (approximately 76%). Nonetheless, the state is firmly in the middle of the pack on other demographic indicators, including household income, educational attainment, and computer/broadband access.

Red State, Purple Dot

No doubt the most famous feature of Nebraska’s electoral system is its method of splitting its five electoral votes. Unlike most states, which award all of their votes to whichever candidate receives a plurality in the state-level popular vote, Nebraska awards just two votes to the statewide winner and one vote to the winner of each of its three congressional districts.

Compared to winner-take-all, this configuration is a boon for Democrats; in 2008 and 2020, Nebraska’s second congressional district awarded one vote to the Democratic candidate. However, the idea that NE-2 is a reliable “blue dot” in the ruby-red state is at least a little overstated. This is a district, after all, that voted for a Republican presidential candidate as recently as 2016 – a district that, to this day, is represented in the House by a moderate Republican. Even in Omaha, the city nominally driving NE-2’s “blue dot” status, the mayor is a Republican and registered Republicans outnumber registered Democrats. As the national electorate calcifies, and “red” and “blue” states become steadily more predictable, the so-called “blue dot” has more in common with the kind of Midwestern battleground that Hopkins described in the wake of the 2016 election: purple, elastic, and torn between urban and rural constituents.

Earlier this fall, Nebraska Republicans, with Trump’s blessing, launched a campaign to re-institute winner-take-all. The push fell short in the state legislature thanks to a pivotal “no” vote from Republican Mike McDonnell, a former Omaha Democrat. McDonnell, however, did not set aside the possibility of changing Nebraska’s electoral vote allocation method in time for the next presidential election.

Elsewhere on the Ballot

Of course, the presidential campaign did not happen in isolation. Nebraska voters faced other important down-ballot choices on Election Day, and the state generally affirmed its preference for Republican officeholders and conservative policies.

Republican Senator Deb Fischer was re-elected over Independent challenger Dan Osborn. Osborn’s middle-of-the-road campaign, which emphasized his nonpartisanship and his working-class roots, made a reasonably competitive race out of what might otherwise have been a slam dunk for Fischer. There are difficulties in drawing analogies between this race and the presidential contest, since both candidates attempted to align themselves with Trump – though only Fischer received his coveted endorsement.

Nebraskans also weighed in on a range of ballot initiatives, and the results are a fascinating mixed bag. Bucking the post-Dobbs trend of enthusiasm for reproductive rights on the ballot, Nebraskans struck down a measure to enshrine a right to abortion in the state constitution and supported a ban for abortions after the first trimester of pregnancy. Interestingly, the margin was substantially lower for the former initiative (3 points versus 10 points) and fewer voters responded to the latter question. Perhaps it was easier to mobilize voters around the relatively clear terms of the ban – which specifies the trimester of concern as well as exceptions for rape, incest, and the health of the mother – compared to the somewhat more vague language of “fetal viability” used in the proposed constitutional amendment.

Nevertheless, voters also opted to require paid sick leave, to legalize medical marijuana (and establish a regulatory body to oversee its usage), and to overturn a law which would provide vouchers to qualified private school students.

Finally, voters in the state’s all-important second Congressional District chose to return Republican incumbent Don Bacon to the House of Representatives. As a testament to the purple-ness of the district, however, Bacon’s opponent, Democrat Tony Vargas, lost by a slim 1.8-point margin.

2024 Campaign Activity

From the beginning, it was clear that NE-2 was a second-rate priority for both the Trump and Harris campaigns. True, there were the inevitable flutterings about how the polls were just so close that it might come down to NE-2’s single vote and national Republicans mustered some strength in their winner-take-all bid, but that energy quickly fizzled.

Although Nebraska spending estimates for the Trump campaign have not yet been released by the Federal Election Commission, Harris allegedly outspent Trump in NE-2, employed more staff members, and ran the lion’s share of presidential campaign ads in the Omaha DMA. Neither candidate held their own rallies in the Cornhusker state, opting instead to send surrogates, including Tim and Gwen Walz, Doug Emhoff, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., and Tulsi Gabbard. Both campaigns had active door-knocking and phone-banking campaigns, with Trump Force 47 – Nebraska’s joint office for the RNC and the Trump campaign – apparently pouring most of its efforts into mobilizing extremely low-turnout voters. Enos and Fowler (2016) argue that ground game activities can in fact mobilize voters who would not otherwise turn out, but this payoff may be tempered by the inefficiency – discussed by Darr and Levendusky (2014) – of contacting rural, low-propensity Republican voters.

Since the Harris campaign was substantially more active in NE-2, and her vote share is the outcome of interest in my model, the suggestions that follow about campaign choices will mostly relate to her candidacy.

Conclusions

Redistricting

My first theory has less to do with voter or candidate behavior, but since it has the potential to explain the discrepancy between 538’s NE-1 and NE-2 prediction errors, I think it is worth mentioning here.

After the release of the 2020 Census, Nebraska’s Republican-run government redrew the boundaries of its three congressional districts. The changes were for the most part subtle, but they involved extending NE-2 further west, into the state’s more rural counties. This change presents a unique challenge for forecasters, whose task mostly involves predicting outcomes in states with long-fixed borders. While 2024 polling in NE-2 should in theory incorporate these newly eligible voters’ intentions (though of course this could be complicated if rural voters prove harder to contact than their urban and suburban counterparts), any historical trends that the model relies on will not be from exactly the same place. Moreover, the suddenness of redistricting makes this a different problem than gradual migration patterns, which all states and districts will have experienced to some extent since 2020.

If 538 did not adequately control for this development – and, as far as I can tell, they do not mention it – their embedded assumptions about NE-2 voters’ behavior could be outdated. For instance, rural voters, given their proximity to the agricultural industry, might be responsive to different economic indicators than Omahans. If that is the case, it could be that new NE-2 voters diluted the relationships that 538’s model was built on, causing the model to overpredict support from Harris. In NE-1, the same story plays out, just in reverse: NE-1 added a few purple areas which previously belonged to NE-2 and dropped portions of rural northeastern Nebraska which swung dramatically to the right in 2024 (see county-by-county swing map, above), which could account for 538 underestimating support for Harris there.

Vavreck’s Campaign Typology

The redistricting explanation does not, however, rule out the possibility that the Harris campaign underperformed in Nebraska. In this section, I will argue that, although Harris did run a loosely-defined insurgent campaign in Nebraska, as recommended by Vavreck (2009) for a candidate in her position, she may have chosen a non-ideal issue.

In both public appearances and private meetings, Harris’s Nebraska surrogates emphasized reproductive rights, making abortion the frontrunner insurgent issue of her campaign in the “blue dot.” This satisfies Vavreck’s requirement that successful insurgents talk mostly about some issue other than the economy, but fares worse on her corollary conditions.

Namely, while abortion is regarded as a strong issue for Democrats nationwide, pro-choice ballot initiatives failed in Nebraska in 2024 and a pro-life Republican kept his House seat in all-important NE-2. In other words, the public opinion on abortion may not be as lopsided in Nebraska as a strong insurgent issue should be, per Vavreck. Vavreck’s typology also states that the clarifying candidate should be hemmed in by an unpopular stance that the insurgent candidate can exploit. While Harris could point to Trump’s nomination of three conservative Supreme Court justices who joined in the decision which overturned Roe, Trump is famously hard to pin down on abortion, so it was no easy task for the Harris campaign to clearly communicate the stakes of a second Trump administration for reproductive rights.

What, then, should Harris have used as her insurgent issue in NE-2? There are at least two plausible contenders, both of which rely on a third, unstated criterion that nevertheless is essential to Vavreck’s thesis: salience. Besides its weaknesses in the corollaries that Vavreck does define, abortion might fail as an insurgent issue simply because it is not top of mind for Nebraskans, several years out from the Dobbs decision. On the other hand, Social Security and candidate quality – or, as Vavreck might say, “traits” – might have helped Harris to catch up with 538’s forecast.

The Washington Examiner conducted a Google trends analysis and reported that Social Security was a top issue for Nebraskans. I should caution that this is a simplistic method of assessing Nebraskans’ priorities that may be overinclusive of non-voters and the report is not transparent about the coding practices used (it may just be easier to code searches for a specific program, like Social Security, compared to a more generic topic like foreign policy or the economy). If, however, we assume that Social Security is a salient issue to Nebraskans, and that those who do care about the program have a lopsided preference for retaining their benefits, then the issue could have been a strong candidate for Harris’s campaign messaging. Admittedly, Trump is once again tricky to categorize on Social Security, but given Nebraskans’ pre-existing frustration with taxes on benefits in their own state under its Republican government, the Harris campaign might have been able to create some useable anxiety among Nebraska voters about what sending Trump back to the White House could do to their benefits.

Bacon – the NE-2 representative who endorsed Trump in 2024 but rejected his efforts to overrule the vote in 2020 – suggested that Trump was ahead with his nonpartisan constituents on policy but behind on “trust.” National Democrats, eager to win Bacon’s seat for themselves, were unsurprisingly uninterested in building a coalition with even the moderates of Nebraska’s GOP (except, of course, when they needed Republican state legislators to shoot down winner-take-all). Perhaps this reticence contributed to shaving down Harris’s margin in NE-2, where campaign messaging focused less on abortion and more on commonsense, democratic governance – an area where Trump is almost certainly committed to unpopular positions – could have lured Trump-weary Bacon voters.

Pork Barrel Spending

Finally, let’s leave Omaha and take a quick detour to Fillmore County in good old NE-3 to discuss a missed opportunity for the Harris campaign to benefit from pork barrel spending.

Fillmore County is rural county that is represented in Congress by Adrian Smith, a self-described “staunch conservative.” Fillmore voted overwhelmingly for Trump in 2024; Harris received just 22.2% of the two-party vote. All of that is to say, it would be farfetched to suggest that the Biden Administration had electoral gains in mind when it allocated a $5.4 million dollar grant to repair rail infrastructure in Fillmore. Yet if we set the administration’s intentions aside, Fillmore presents an interesting case study for the pork barrel theory articulated by Kriner and Reeves (2012).

Kriner and Reeves argue that pork is most effective at increasing support for the incumbent party when the county benefiting is represented in Congress by a copartisan of the president, when the funding is given to a swing state, and when it is clearly communicated to voters that the incumbent party was responsible for the grant. None of these conditions appear to have been satisfied in the case of Fillmore’s grant: Smith is not a Democrat, Nebraska — NE-2 aside — is not a battleground, and an article in the Nebraska Examiner announcing the funding spends about as much time referencing Nebraska’s Republican Senators as it does the Biden Administration. It should come as little surprise, then, that Fillmore swung to the right in approximately equal measure to its neighbors in 2024 (see county-by-county swing map, above).

To make a robust causal argument about the impact of federal funding on the vote in Fillmore would require a thoughtful matching procedure and should might be better analyzed at the precinct level. By mentioning this case, I mean only to raise the possibility that a lack of clarity about the Biden Administration’s involvement in federal grants could have contributed to Harris’s slight underperformance statewide relative to 538’s prediction.

Thank You

Thank you for joining me this semester and on this detour into Nebraskan politics!

References

270toWin. (n.d.) Nebraska. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://www.270towin.com/states/Nebraska

Ballotpedia. (n.d.) Nebraska elections, 2024. Accessed December 7, 2024. https://ballotpedia.org/Nebraska_elections,_2024

Ballotpedia. (n.d.) Redistricting in Nebraska after the 2020 census. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://ballotpedia.org/Redistricting_in_Nebraska_after_the_2020_census

Boyd County, Nebraska. (2024, November 6). Summary Results Report. https://countyelectionresults.nebraska.gov/election_files/Boyd/2024_General_official_results.pdf

CNN Politics. (n.d.) Nebraska President Results. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://www.cnn.com/election/2020/results/state/nebraska/president

Cook Political Report. (2024, November 4). 2024 CPR Electoral College Ratings. https://www.cookpolitical.com/ratings/presidential-race-ratings

Darr, J. & Levendusky, M. (2014). Relying on the Ground Game: The Placement and Effect of Campaign Field Offices. American Politics Research, 42 (3), 529-548. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X13500520

Deuel County, Nebraska. (2024, November 6). Summary Results Report. https://countyelectionresults.nebraska.gov/election_files/Deuel/2024_General_official_results.pdf

Enos, R. & Fowler, A. (2018). Aggregate Effects of Large-Scale Campaigns on Voter Turnout. Political Science Research and Methods, 6 (4), 733-751. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2016.21

Federal Election Commission. (n.d.) Campaign finance data. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://www.fec.gov/data/

FiveThirtyEight. (2024, November 5). Who Is Favored To Win Nebraska’s 1st District’s 1 Electoral Vote? ABC News. https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/2024-election-forecast/nebraska-1/

FiveThirtyEight. (2024, November 5). Who Is Favored To Win Nebraska’s 2 Electoral Votes? ABC News. https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/2024-election-forecast/nebraska/

FiveThirtyEight. (2024, November 5). Who Is Favored To Win Nebraska’s 2nd District’s 1 Electoral Vote? ABC News. https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/2024-election-forecast/nebraska-2/

FiveThirtyEight. (2024, November 5). Who Is Favored To Win Nebraska’s 3rd District’s 1 Electoral Vote? ABC News. https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/2024-election-forecast/nebraska-3/

Gilsinan, K. (2024, October 14). The Battleground Where Harris Is Drubbing Trump. Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2024/10/14/nebraska-2nd-district-battleground-00183400

Gonzalez, C. (2024, October 29). Federal $5.4M grant to help rehab rail line in Nebraska’s Fillmore County. Nebraska Examiner. https://nebraskaexaminer.com/briefs/federal-5-4m-grant-to-help-rehab-rail-line-in-nebraskas-fillmore-county/

Hoff, M. (2024, September 12). All eyes are on Nebraska’s ‘blue dot,’ which could determine who wins the White House. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/elections/2024/09/12/2024-presidential-race-nebraska-blue-dot/75018361007/

Hopkins, D. (2017). Red Fighting Blue. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108123594.006

Kimball County, Nebraska. (2024, November 6). Kimball County General Election Results. https://irp.cdn-website.com/82f946ac/files/uploaded/General_Election_Results-Pres_2024-c4b5ed95.pdf

Koons, C. (2024, December 5). Latest 2024 farm income forecast shows overall decrease from 2023. Nebraska Examiner. https://nebraskaexaminer.com/2024/12/05/latest-2024-farm-income-forecast-shows-overall-decrease-from-2023/

Kriner, D. & Reeves, A. (2012). The Influence of Federal Spending on Presidential Elections. The American Political Science Review, 106(2), 348-366. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055412000159

Lee, C. (2024, November 6). How the 10 States’ Abortion Ballot Initiatives Fared in the 2024 Election. TIME Magazine. https://time.com/7173410/abortion-ballot-results-2024-election/

Luhby, T. (2024, November 13). How a second Trump term could affect Social Security benefits. CNN Politics. https://www.cnn.com/2024/11/13/politics/benefits-trump-social-security-plan/index.html

McLoon, A. (2024, November 4). Election Week: The presidential ground game in Omaha. KETV NewsWatch 7. https://www.ketv.com/article/election-week-the-presidential-ground-game-in-omaha/62798017

Mondeaux, C. (2024, November 4). Why a Dan Osborn victory in Nebraska Senate race may not be a win for any party. Washington Examiner. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/news/campaigns/congressional/3214917/dan-osborn-nebraska-senate-race-independent/

Morris, G. (2024, August 23). How 538’s 2024 presidential election forecast works. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/538/538s-2024-presidential-election-forecast-works/story?id=113068753

Murray, I. (2024, October 20). ‘Blue Dot’ in Nebraska draws boldface political names. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/blue-dot-nebraska-draws-boldface-political-names/story?id=114967525

Napier, A. (2024, October 24). Election 2024: Here are the issues Nebraska voters care the most about. Washington Examiner. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/news/campaigns/presidential/3195453/2024-election-nebraska-voters-issues-abortion-social-security/

Nebraska Secretary of State. (2024, November 26). Election Results. https://electionresults.nebraska.gov/resultsCTY.aspx?type=PC&rid=12465&osn=93&map=CTY

Nir, D. (2022, November 14). Daily Kos Elections’ 2020 presidential results by congressional district. Daily Kos. https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2012/11/19/1163009/-Daily-Kos-Elections-presidential-results-by-congressional-district-for-the-2012-2008-elections

NPR. (2024, December 5). Nebraska Election Results. https://apps.npr.org/2024-election-results/nebraska.html?section=P

Sanderford, A. (2024, August 10). Nebraska’s 2nd District steps back into presidential spotlight after crazy month. Nebraska Examiner. https://nebraskaexaminer.com/2024/08/10/nebraskas-2nd-district-steps-back-into-presidential-spotlight-after-crazy-month/

Sanderford, A. (2024, October 5). Gwen Walz stops in Nebraska to stump for reproductive rights, Dems. Nebraska Examiner. https://nebraskaexaminer.com/2024/10/05/gwen-walz-stops-in-nebraska-to-stump-for-reproductive-rights-dems/

Sanderford, A. (2024, October 13). Tim Walz coming back to Nebraska’s 2nd District for Harris on Oct. 19. Nebraska Examiner. https://nebraskaexaminer.com/briefs/tim-walz-coming-back-to-nebraskas-2nd-district-for-harris-on-oct-19/

Sanderford, A. (2024, September 23). State Sen. Mike McDonnell deflates GOP hopes for Nebraska winner-take-all in 2024. Nebraska Examiner. https://nebraskaexaminer.com/2024/09/23/state-sen-mike-mcdonnell-deflates-gop-hopes-for-nebraska-winner-take-all-in-2024/

Schleifer, T. (2024, September 17). Presidential Campaigns and Allies Plan $500 Million in TV and Radio Ads. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/17/us/elections/presidential-campaign-advertising-spending.html

United States Census Bureau. (n.d.) Quick Facts: Nebraska. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/NE/PST045223

Vavreck, L. (2009). The Message Matters: The Economy and Presidential Campaigns. Princeton: Princeton University Press. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/36264